The love of words...

When I was a boy, among the favourite books on my shelf were the blue cloth-bound volumes of Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedia. The love of words was there from the beginning, and I always knew how fortunate I was in my father who was constantly bringing home for me illustrated books that he’d picked up cheaply from the second-hand shops.

When I was a boy, among the favourite books on my shelf were the blue cloth-bound volumes of Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedia. The love of words was there from the beginning, and I always knew how fortunate I was in my father who was constantly bringing home for me illustrated books that he’d picked up cheaply from the second-hand shops.

Robin Hood, Mother Goose … some of them now very valuable and given to me, far too young, to scribble upon. Three beautiful volumes of Robert Louis Stevenson, illustrated by N C Wyeth, which I still have, unscribbled and treasured every bit as much as Jim Hawkins’ island.

Of all my books, the ones I kept returning to, as the world began to open to me, were the Encyclopedias – their covers lettered in gold, as I remember, and the glossy pages filled with pictures and articles on a vast array of subjects. The story of steam … aeroplanes … the great musicians, Handel and Mozart, who I was learning to torture on the piano … chemistry … battles … famous people … kings and queens in history …

It never ceased to surprise me that the world could contain so much knowledge … or indeed so many words.

Daniel Defoe

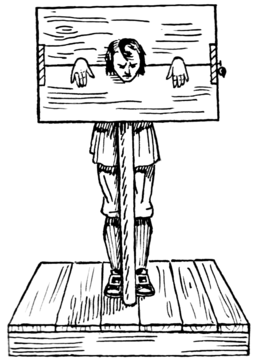

One of the pictures that remained most vividly in my memory, was a painting of the author and early journalist Daniel Defoe (he of Robinson Crusoe) standing in the pillory as punishment for words he’d written that offended those in authority. I can still see it: Defoe’s head and hands clamped in a wooden frame, like the stocks, as he stood in the public street on and off for three days – though the passers-by, at least in legend, far from reviling and pelting him with garbage, threw flowers instead.

One of the pictures that remained most vividly in my memory, was a painting of the author and early journalist Daniel Defoe (he of Robinson Crusoe) standing in the pillory as punishment for words he’d written that offended those in authority. I can still see it: Defoe’s head and hands clamped in a wooden frame, like the stocks, as he stood in the public street on and off for three days – though the passers-by, at least in legend, far from reviling and pelting him with garbage, threw flowers instead.

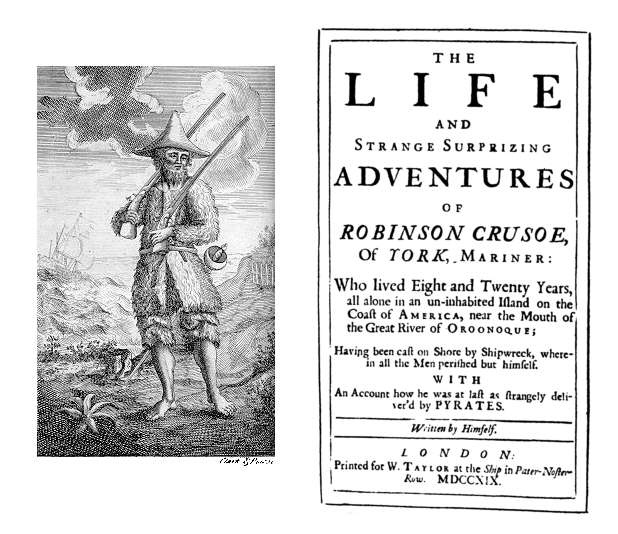

Defoe’s offence was to publish a pamphlet called The Shortest-Way with Dissenters. Religious toleration was under some threat from Queen Anne in 1703; and Defoe proposed that the best thing to do with Non-Conformists like himself, was to crucify them. It was intended as a satire in the vein later followed by Swift in his Modest Proposal (suggesting that the way to solve Irish poverty was to eat the children of the poor.)

Irony and satire is a dangerous weapon to use in political debate. People can take you seriously. Or pretend to. Which is what happened to Defoe. The politician, Robert Harley, arranged to have him prosecuted for criminal libel. Hence the pillory and months in prison before Harley, in the devious way of his kind, arranged for Defoe’s release, paid some of his debts, and employed him as an agent in Scotland during the public controversies over the Act of Union.

It’s certainly true that Defoe went on to found the periodical Review, considered the first modern newspaper, and of course wrote the first great modern novel in Robinson Crusoe. But it was always said that he never fully recovered psychologically from the humiliations of his punishment, which one can well believe.

I can’t say that my childhood sympathy with the plight of Daniel Defoe was the specific that encouraged me into journalism and the desire one day to write my own novels. No doubt it was one among many factors that led me to that path.

But I do know that the picture of Defoe in the pillory has been very much in my mind in recent times, observing the debates in Australia and Britain to tighten the regulation of the press. It has been dreadfully depressing to see judges and governments – of various political persuasions – proposing ways to curb the freedom of journalists to say things that other people might not like, in a manner that we’ve rarely seen (outside of war) since the time of Defoe himself. Liberty has enough of a struggle to defeat its enemies, than have to confront its friends as well.

Media excess

It’s understandable that many British people want to rein in the media excesses that were there exposed in the phone hacking scandals. And something has been done: certain journalists and other individuals alleged to have used illegal phone taps or resorted to bribery have been charged and are before the courts. This is as it should be for anyone who has broken the civil or criminal law. People whose privacy has been breached have sought and, I understand, are obtaining compensation. Do they really need another media regulator established by Royal Charter, with exemplary damages for those organisations that don’t subscribe to it? More punishments? More bridles?

In Australia no such wholesale breaches of the law have been alleged. One struggles to find a reason for the wave of regulatory passion other than a desire to curb anti-government criticism. And yet after one media enquiry conducted by a judge and a year of cogitation, legislation has been introduced that will surely circumscribe the freedoms of the media, amid demands that it pass the Parliament within a couple weeks and a minimum of consideration.

Negotiations are continuing at the time of writing. But of particular concern is the appointment of a Public Interest Media Advocate (PIMA), a part-time official, independent of the Minister but reliant to a large extent on his public servants. This functionary will have extraordinarily wide powers, not subject to judicial appeal except on administrative grounds:

* The PIMA will ‘declare’ or authorise media self-regulating bodies, such as the Press Council, according to whether they uphold ill-defined and constantly changing ‘community standards’ of fairness. Such bodies of course can be un-declared and un-authorised, in which case the journalists and their employers will lose their right to protection under the Privacy Act.

Anyone who thinks this will not be an incentive for journalists and the media to restrict their reporting and opinions to what PIMA may consider acceptable, does not understand the nature of coercion. And governments do not appoint unsympathetic Public Interest Advocates of any kind, especially if they have no control over them.

* The PIMA will review and have power to approve or block transactions which it considers may substantially lessen diversity of control in the news media (print, broadcasting and online), and can force shares to be disposed of where the public benefit (however subjectively one defines it) is not considered to outweigh the change in control.

This in the digital age, where everyman can be his own media boss. Still, you can’t help feeling that this seems to be a return to licensing of the press under another guise … and even in Daniel Defoe’s time that particular form of control had fallen into disuse. From 1695 the authorities preferred to rely on the use of criminal libel to silence critics, as Defoe of course found to his cost when he wrote The Shortest-Way with Dissenters.

Criticism

It’s certainly true that the present Australian government has been subject to sustained criticism especially from the News Ltd papers, (whose editors would argue there’s been much to be critical about.) Some of it’s undoubtedly been ‘over the top’, as witness the Sydney Telegraph front page cartoon depicting Minister Conroy, on the day he unveiled his bills, in the same company as Stalin and Chairman Mao.

But the answer to that is not more regulation, but civil action for libel if the minister felt so affronted. In my time as a journalist many a public figure boasted of the billiard rooms, swimming pools and jacuzzis paid for courtesy of one or other media company in generous out-of-court settlements.

Even better in this case, one reads, the minister apparently laughed – said he expected no other – and signed copies of the front page for his friends. Daniel Defoe might have wished that Robert Harley had responded to his polemic with such sang-froid.

The clash of opinions

For in the long run it is only from the clash of strongly-held opinions, boldly expressed … the contest of ideas in the public forums, magnified, illuminated and broadcast molto crescendo in the media … that concepts of social truth, fairness, and acceptance of change will emerge. The strength of a liberal polity comes not from the unity of its voice – not from some arbitrarily imposed ‘community standards’ – but from the diversity of argument and opinion within it.

For in the long run it is only from the clash of strongly-held opinions, boldly expressed … the contest of ideas in the public forums, magnified, illuminated and broadcast molto crescendo in the media … that concepts of social truth, fairness, and acceptance of change will emerge. The strength of a liberal polity comes not from the unity of its voice – not from some arbitrarily imposed ‘community standards’ – but from the diversity of argument and opinion within it.

The great invention of the British Parliamentary system was the idea of a ‘Loyal Opposition’, still emerging at Westminster in Defoe’s age from the conflict of civil and religious war. It’s something that many ex-colonial states, for all they adopt the trappings of wigs, Speakers and maces, have trouble understanding.

But by God I would rather have the uproar of Question Time in our Parliament any day over the frightened, clapping unanimity of some totalitarian’s National Assembly.

I don’t know what, in the present debate, I’ve found the sadder: watching a group of journalists laugh at a colleague on television who was defending with some passion their freedom of speech from the proposed legislation … or listening to certain politicians and public personages complain that it doesn’t go far enough.

They really want to be careful what they wish for. Because sooner or later they’ll find themselves on the wrong side of prevailing opinion and community standards. And all too late they’ll discover that the new pillory they’ve helped to erect in the town square is waiting for them.

FOOTNOTE: Since writing this article the four most contentious media Bills have been withdrawn from Parliament through lack of cross-bench support. The new Attorney-General has also announced that a proposed anti-discrimination package of amendments would be reconsidered. The draft legislation would have made it unlawful to offend somebody on grounds of their political opinions (!), among other things, and reversed the onus of proof once a prima facie case had been established. For these developments, much thanks.

Picture credits:

The Politician by William Hogarth: 19th century copy in author's possession.

Daniel Defore in 1706: Wikipedia commons.

Robinson Crusoe first edition, 1719: Wikipedia Commons.

The Pillory, by Pearson Scott Foresman: Wikipedia Commons.