After the Interview

We've done the interview. We've made sure the conversation has been safely recorded. We've jotted down notes of the important points as we went along.

Now, alone at the desk and ready to transfer these golden nuggets of research into our book, the question arises: What next?

Far be it from me to tell fellow authors how to suck eggs. We all have our own ways of doing things, and there is no right or wrong of it. The end result is all that's important. But from long experience there are a few tips worth passing on, which may be of use both to novices as well as established writers.

Do it quickly

Try to complete the précis or transcript of the interview as soon as possible. There are a couple of reasons for this: firstly because it gets done what can sometimes be an arduous task, and secondly because a close listening of the interview may sometimes open new lines of enquiry...

Try to complete the précis or transcript of the interview as soon as possible. There are a couple of reasons for this: firstly because it gets done what can sometimes be an arduous task, and secondly because a close listening of the interview may sometimes open new lines of enquiry...

To say nothing of the disaster that can arise if something has gone wrong with the recording ... that the tape has jammed at a critical point ... the machine "record" button failed ... or, as has occurred to me often enough, that I've inadvertently erased the recording as I've been transcribing. It happened twice when I was going over the interviews with Billy Young.

At least if the interview is still fresh in your mind you can put down the salient points from memory ... even if, in the finished work, you might have to rely on an indirect quote rather than verbatim speech. Hence the importance of the notes you've taken during the interview – and the undoubted safety given by both "belt and braces" in the matter of authorial security.

Should I transcribe it all?

It's a question of individual choice, but in the interests of time I rarely do. Certainly when we get to the meat of the interview I will transcribe it word for word. But I’ll usually précis down minor points, or repetitions, and simply note topics of conversation, in case I need to refer to them later on during the writing.

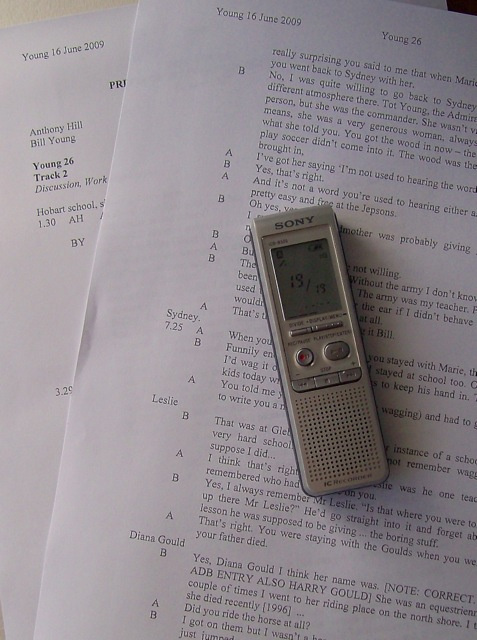

I did more than 60 hours of interview with Bill Young, and I made pretty much a full transcript of the first conversations. Towards the end, when we were going over points of detail, I relied much more heavily on the précis, except when Billy remembered new material, or the conversation strayed into unfamiliar territory, as it will when we venture deeply into our subject's memory.

Whether it's a full or partial transcript, however, I've always found it very helpful to write down on my notes the time that significant matters arise during the interview, so that I can refer back to the material quickly if I need to, without having to scroll through an entire recording.

Keywords and files

In a similar way, I find it useful to note the topic of conversation or a keyword in the margin of the transcript. It makes it much easier to collate the material on significant subjects when it comes composing – especially during long or multiple interviews, as with Bill Young, where the subject matter can switch constantly.

In a similar way, I find it useful to note the topic of conversation or a keyword in the margin of the transcript. It makes it much easier to collate the material on significant subjects when it comes composing – especially during long or multiple interviews, as with Bill Young, where the subject matter can switch constantly.

In his case I kept a running transcript of each interview, numbered, dated and paginated (there were ultimately over 300 pages), and of course kept a copy of each recording on the computer.

As it was a biography of this underage soldier, I also used the computer to create separate files on each of the significant episodes in his story: childhood, joining up, the war in Malaya, the POW camp at Sandakan, Outram Road prison, post-war.

Here, the keywords were invaluable in copying and pasting the sections of transcript into the new files. It's important, though, to note which interview they've come from for future reference.

Should I show the transcript?

This is another question that ultimately is a matter of choice. In my case I never do, unless the person specifically asks to see it. The reason is that people sometimes give confidences in an interview that may be important ... yet may well resile from them if they see the material set out baldly without any context. Or they may be self-conscious to see their words written down.

Of course any request during an interview to treat a particular topic as being "off the record" must be respected absolutely. Several times, during my talks with Bill Young, I turned the recorder off at his request.

But with this exception, by and large I find it much better to show my subject the relevant section of text once it has been put into literary form and set within the context of the whole narrative.

Some writers think even this is going too far; but if we want our books to endure I think it important to give people the opportunity to correct matters of fact, and at least to have the chance to offer an alternative view when it comes to questions of interpretation.

Besides, you never know where it will lead. Billy Young read his story chapter by chapter as I completed them. And it was extraordinary how often, when he saw his past coming to life on the page, the experience would trigger more memories ... more material to enrich and deepen what was already a dramatic episode in the history of his life and that of the Second World War.

Which is something, surely, that as writers and researchers, we are all striving to achieve.

* * *

Next week: Celebrated Australian radio broadcaster, Tim Bowden, begins a series of guest posts reflecting on his long experience of interviewing using oral history techniques.

P.S. And perhaps have a look at my recent eBook Growing Up & other Stories on Kindle with the companion volume Discovery & Other Stories. Growing Up was a Children's Book Council of Australia Notable Book.

Until then

Anthony

Photo credits:

Transcript from The Story of Billy Young research: author photo.

The Story of Billy Young cover: courtesy Penguin/Viking.

Bill Young today: photo by John Feder.