|

Background article

THE IDEA OF ISAAC

Endeavours of an author

By Anthony Hill

Germ of an idea

Where do get your ideas? It’s the question every author is most frequently asked: and the answer is no less elusive than it is obvious. For the truth is that ideas for books are all around us. A word, a thought, an image, an anecdote… The merest glimpse and suddenly, to a receptive mind, there it is: a book already finished in the imagination, whole and perfect in a way that is never actually realised – although the vision remains to sustain you through the months and years of labour ahead.

In the case of my new novel Captain Cook’s Apprentice – very much a mess deck view of the Endeavour voyage – the idea came from a stray sentence in a book.

Spirit of New Zealand in Queen Charlotte Sound

As a writer of historical fiction, I’ve less time to read purely for pleasure than I could wish. It’s mostly work. But in a rest between projects in early 2003, I was reading J.C. Beaglehole’s Life of Cook when I found a brief reference to a boy named Isaac George Manley. As a writer of historical fiction, I’ve less time to read purely for pleasure than I could wish. It’s mostly work. But in a rest between projects in early 2003, I was reading J.C. Beaglehole’s Life of Cook when I found a brief reference to a boy named Isaac George Manley.

He’d joined Endeavour as a young servant, was appointed a midshipman on the return voyage, rose to become an admiral, and when he died at the great age of 82 was the last survivor of the Endeavour crew.

Rest and recreation went out the window. I put down the volume, said to myself, ‘Now there’s an idea’, and fantasised that I was holding the completed book in my hand. If you are lucky, at such moments, you can even see a title. I’m afraid the name of Isaac’s book was still quite blank to my eyes, and would take years to discover. Still, I looked him up on the Internet; found a mention at the National Library; and put the idea away in a safe, dark place to develop, like yeast in a covered bowl.

The dough rises

It was two years before I looked at it again to see if the dough had risen. The initial inspiration of a book is rarely a single idea. Contained within its imagined pages are a multitude of subsidiary ideas: themes, approaches, plot, sub-plots, illustrations, perhaps even words or phrases might all be hinted at. And returning to see if the mixture left to stand had ‘proved’ itself, I was delighted to find that what first excited me about Isaac’s story had indeed grown. It was time to roll up the sleeves and get down to serious kneading. For there was much to be done before even the first words could be written on the physical page.

I’ve always sought to base biographical novels as closely as possible on the historical record. Accuracy is everything, a legacy no doubt of my years in journalism. To be sure the novelist has to make assumptions where the record is silent, and of course the internals of character, thought, speech and emotion can come only from the author. But where some writers may change the external facts to suit their story, I must change my story to fit the known facts.

Since very little beyond the briefest mentions had been published about Isaac Manley – and some of those turned out to be wrong, for even his obituary managed to confuse Isaac with somebody else – it was clear that Captain Cook’s Apprentice would involve a great deal of research. It meant extensive reading of the more recent literature at home, and much older volumes at the National Library of Australia, where I was given a very great privilege.

A rare privilege

Early in my work the-then manuscript librarian, Graeme Powell, allowed me to sit for four hours with Cook’s handwritten Endeavour journal. We can all virtually do the same now with the online version of this national treasure. Isaac’s name doesn’t appear in its pages, although he is mentioned in the muster book and in Cook’s letter recommending him to the Admiralty when they returned to England.

But reading the Captain’s clear, sepia-stained words I was in immediate contact with the great adventure, as day by it unfolded with all of Cook’s idiosyncratic spelling on the ‘high rowling sea.’ I could see the gradual transformation of Stingray Harbour to Botanist Harbour and finally to Botany Bay, or a much later insertion ‘by the ‘name of New South Wales’… and the idea of my book began to turn into reality. I could even sense Isaac’s unseen presence slipping between the inky lines.

Such a book needs more than wide reading, however. For me it also requires a lived experience, the primary resource of any writer. And that meant a good deal of expensive travel, which I am indeed grateful that a grant from the Australia Council for the Arts made possible.

Journeys

I had to go to England to look for the documentary evidence of Isaac’s naval career in the National Archives and other repositories. The National Maritime Museum and the British Library are essential for anyone interested in Captain Cook and the Royal Navy. And I wanted to see for myself what remains of the world Isaac Manley knew.

Braziers, the garden front

He prospered in life. Braziers, the lovely Oxfordshire house Manley remodelled in 1795 in the Strawberry Hill gothic style, is still standing and open for visitors to stay. Sitting beside his fire, living for a few days in the rooms he inhabited, the man’s presence became far more tangible. He prospered in life. Braziers, the lovely Oxfordshire house Manley remodelled in 1795 in the Strawberry Hill gothic style, is still standing and open for visitors to stay. Sitting beside his fire, living for a few days in the rooms he inhabited, the man’s presence became far more tangible.

You could see how he ordered his life. I met one of Isaac’s descendants. I spoke at the annual meeting in Yorkshire of the Captain Cook Society, whose members have been infallibly helpful with my enquiries. But in three years of research I have been unable to find anything Isaac himself wrote about the Endeavour voyage.

It was of course necessary to go to Tahiti and New Zealand, for how can you write about the islands of the South Seas if you haven’t been there? This is not a self-justification for an exotic holiday (although it’s nice if the idea takes you there). But for me the colours, smells, sounds and sensations of place influence everything I write when trying to re-create a scene: seeping through the words, so that for a reader the experience may become an authentic one.

Nor was it just a matter of location. Part of the idea was to give today’s young readers a sense of what it was like to voyage on an 18th century ship – and for that I sailed on the Endeavour replica in April 2006 from Melbourne to her home berth at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney.

Aboard Endeavour

I went as a full fare-paying passenger, unsure how much a 64-year-old landlubber could manage as a part of the working crew. In fact I did most of what I wanted. I served with my watch (although I was allowed to lie abed some early mornings). I climbed 30-feet up the foremast. I stood my ‘trick’ at the wheel. I hauled lines, and swabbed the deck. I went as a full fare-paying passenger, unsure how much a 64-year-old landlubber could manage as a part of the working crew. In fact I did most of what I wanted. I served with my watch (although I was allowed to lie abed some early mornings). I climbed 30-feet up the foremast. I stood my ‘trick’ at the wheel. I hauled lines, and swabbed the deck.

I also had the only bunk aboard, in Mr Banks’s cabin: but as Isaac slept in a hammock in the 4ft-6in section of the mess deck, I swapped one night with a woman crew member. It was enough. I felt like a sausage distended in its skin: slung on a hook, swinging supine on my back. They say it takes three nights to sleep in a hammock, after which you’re so exhausted you’d flake anywhere! I took their word for it.

I sailed two stages – Melbourne to Eden, Eden to Sydney – fearing I’d be seasick on the first leg, but hopefully come good on the second leg. So it transpired. I poured my heart into stormy Bass Strait. But that, too, is part of it. And I got my reward as I went on deck at dawn on the fourth day, and Captain Ross Mattson pointed to a smudge on the grey horizon. ‘That’s Point Hicks,’ he said. And I had one of those rare moments of epiphany. For me and my family, I thought, this is where it all began: with Zachary Hicks sighting Endeavour’s first landfall in New Holland on such another April morning in 1770.

Why another 'Cook book'?

Now this raises a fundamental question about my ideas for this book that I had to resolve before undertaking any of this adventuring. Why bother? Why another ‘Cook book’? There’s scarcely a month goes by without a new publication about the Captain, so why add to the pile?

Coconut palms, Tahiti

Adventures. It’s true that world-wide interest continues unabated in Cook’s three Pacific voyages of exploration. The television series in 2007 by Vanessa Collingridge served to stimulate it even further. And it’s certainly true that the Endeavour voyage in particular was a tremendous adventure… Adventures. It’s true that world-wide interest continues unabated in Cook’s three Pacific voyages of exploration. The television series in 2007 by Vanessa Collingridge served to stimulate it even further. And it’s certainly true that the Endeavour voyage in particular was a tremendous adventure…

Death in the snows of Tierra del Fuego. The sensuous delights of the earthly Venuses at Tahiti – no less than observing the transit of the heavenly one. Maori warriors and cannibals in New Zealand, Charting the east cost of New Holland, and first meetings with Aborigines. Near-disaster on the barrier reef – and real tragedy waiting in Indonesia, where disease killed a third of the crew, and gave Isaac his opportunity for promotion. When the survivors reached England in July 1771, they must have returned as space voyagers would today, as if from another planet.

Discoveries. The results in so many branches of science were truly breathtaking. Endeavour brought back over 1000 botanical specimens unknown in Europe, among them the first eucalypts and banksias. There was the skin of the first kangaroo. Sydney Parkinson’s beautiful paintings of people, places and species barely heard of.

The astronomical observations of the Transit of Venus at Tahiti were critical in determining the Earth’s approximate distance from the Sun. Detailed descriptions of native societies by Cook and Banks laid the foundations of modern anthropology.

Above all, it came to be realised that the outlines of the remaining habitable portions of the globe had been filled in, apart from some Pacific islands many of which Cook charted in his later voyages. This in turn led to the European colonisation of Australia, New Zealand and Oceania, with all that was to follow over the next two centuries.

Precursors. In a very real sense the Endeavour voyage was a precursor to the modern histories of this part of the world. For many people it is now seen mainly in these terms – though whether for good or ill depends on the individual point of view. For some, it laid the foundations of those liberal, prosperous democracies that my family has known through five generations. For others, Endeavour men were the forerunners of invaders who would largely destroy the indigenous societies they encountered.

First contacts. Cook was not unaware of this dilemma. When he learned that Europeans had introduced venereal disease to Tahiti, he wrote in his Journal that it would eventually spread through the south seas, ‘To the eternal reproach of those who first brought it among them.’ Reproach is scarcely a strong enough word for many artists and writers who look at Cook and Endeavour from a contemporary indigenous standpoint.

Whatever your view, it nevertheless seems to me that in many ways the sheer adventure of the Endeavour story has been rather lost under its subsequent histories and interpretations. We discern the highlights: but the rest has become obscured, like an old painting hidden under layers of varnish.

The idea of Captain Cook’s Apprentice has been to respectfully peel away those layers to show young readers the vibrant colours of the original as they first appeared. And since all history is narrative, I’ve sought not only to re-tell the story for a new generation through young eyes, but also to recapture something of the excitement of the tale as it was when people first heard it.

The other side of the beach

Not that I by any means ignored the indigenous perspective. The ‘view from the other side of the beach’, as it’s been called, is an essential part of the idea. Endeavour men who returned to London as if from another planet, appeared no less alien to the native people who looked upon white-skinned beings for the first time: many of them with great fear – and bravery – to confront what may have been the spirits of the ancestors.

There is surely no scene in the whole literature more poignant with foreboding and courage than the two Gweagal warriors who faced Cook’s boatloads of armed men with shield and fighting spear on the sandstone ledge at Gamay – Botany Bay. ‘Warra! Warra Wai!’ Go away. Go far away.

In this part of the research, I was extraordinarily lucky with the people who shared their knowledge and understanding of traditional life with me.

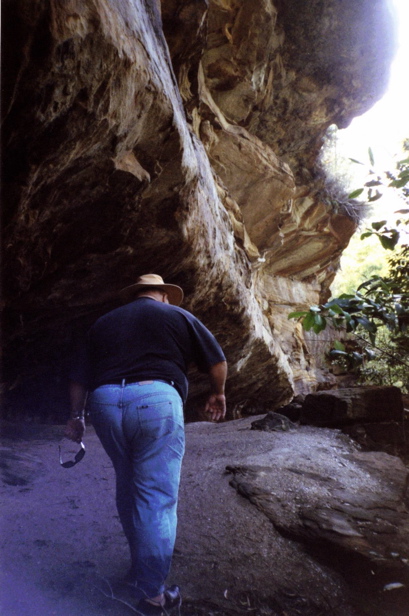

Aborigines I met Les Bursill, an Aboriginal man of the Dharawal people from the southern side of Botany Bay, through my friends Margaret and Ron Simpson of the Captain Cook Society. Together we spent a magical day on Port Hacking, as Les showed us aspects of Aboriginal society still there to be seen by those who know how to look. Camp sites, shell middens, fishing holes, a canoe tree, paintings and carvings on sandstone overhangs hidden by the bush … all within the area of metropolitan Sydney. Aborigines I met Les Bursill, an Aboriginal man of the Dharawal people from the southern side of Botany Bay, through my friends Margaret and Ron Simpson of the Captain Cook Society. Together we spent a magical day on Port Hacking, as Les showed us aspects of Aboriginal society still there to be seen by those who know how to look. Camp sites, shell middens, fishing holes, a canoe tree, paintings and carvings on sandstone overhangs hidden by the bush … all within the area of metropolitan Sydney.

Les Bursill at Port Hacking, NSW

At Cooktown I was in contact with Eric Deeral, an elder of the Guugu Yimithirr people, and was able to draw on his written statements of Cook’s only extended contacts with Aborigines. He’d beached Endeavour for repairs at Wahalumbaal birri [Endeavour River] after running aground on the reef, and relations at first were amicable – until a dispute over turtle meat led to shootings and a grassfire. Again, through Willie Gordon and the Hopevale community I was given a profound insight into the realities of the traditional ‘sharing code’, as powerful now as it was then.

Maori. In New Zealand, I was fortunate to meet Peter Johnston who offered a thoughtful and balanced Maori view of Cook’s generally peaceful time with the Ngati Hei people at Whitianga [Mercury Bay], after the bloody first encounters at Poverty Bay.

And at Queen Charlotte Sound I had another enchanted day on the water with Pete and Takutai Beech. Sailing among the islands and grey-green shores that evoke memories of the Scottish lochs, you can understand why Cook came here to rest and repair his ships on each of his three Pacific voyages.

Pete and Takutai also eased my way into one of the more delicate subjects I wanted to discuss: cannibalism.

Endeavour men nicknamed the Sound ‘Cannibal Bay’, because it was here they first saw irrefutable proof of the practice – though you don’t find that mentioned very often now. But as soon as I spoke of my interest in Cook, Pete and Takutai said they’d take me to Grass Cove, where a boat full of men were killed and eaten on Cook’s second voyage. It’s the mainspring of Anne Salmond’s recent book The Trial of the Cannibal Dog.

Red meat. I should add that the day’s culinary research involved more than humankind. At Grass Cove Takutai showed me some of the few remaining patches of wild celery, eaten by Cook’s men as an anti-scorbutic. And on Arapawa Island we visited Betty Rowe, who gives sanctuary to descendants of the Tahitian pigs and English cottage goats landed by Cook to provide an alternative source of red meat. For rats and little South Sea dogs were the only other mammals living with the Maori on Aotearoa. The pigs, incidentally, are still known as ‘Captain Cookers’, as they are in North Queensland: another small detail to emerge from my travels.

Writing Captain Cook's Apprentice

Still, you cannot go on just accumulating details, however fascinating. There comes a time when the research has to be put to one side, and the ideas translated into the first words of a novel on the page. I was lucky there, too.

First words. I always knew the story would begin with Isaac going down river to join his ship at Deptford. And early on the morning of Boxing Day 2006, the opening words entered my consciousness. The boy knew danger was coming… I got up, crept to the other end of the house, and wrote them on a piece of paper. The second sentence attached itself. Then a third. I transferred them to the laptop, and the discipline necessary to every writer re-established itself. The harness slipped back on.

Writing techniques. Every morning, when composing, I write a minimum of 200 words – often more, but never less. I might complete a passage or a train of thought, but always I stop when I know what the next words are going to be. The rest of the day is thinking about them – often dreaming them at night – so that when I wake in the next dawn the ideas are ready to be written down. And every day one more page is added to the pile.

Thus I try to avoid the horrors of a wordless black hole. And thus over the next nine months, consulting the research filed in chapter folders, re-reading the Journals of Cook and Banks for accuracy, I completed my own circumnavigation of the ideas for this book. For in a way that doesn’t often happen, when I wrote down those opening words I knew exactly what the closing lines would be. So, one September morning, with a sense of excitement, fulfillment and sadness I came full circle and typed them out. Had my little cry. And dropped anchor once more in home waters.

Last words. There was of course much more to be done. A short ‘Afterwards’ chapter had to be written, for early ideas that the novel might cover Isaac’s later life had to be discarded, and the story concentrated wholly on the Endeavour voyage. The first draft had to be revised, cut and re-written before a second draft was ready for the publisher. This turned into a third draft, which went through the long process of editing, designing and proofing by which ideas are manufactured into a book. Patrick White called it the ‘oxy-welding.’

Finding the title. We had to find a title. For years I’d been calling the book Admiral Isaac, although I knew that wasn’t right. I always felt it was somewhere in the text – but it took a young trainee at Penguin to discover it. There it was on page 18 of the typescript: Every officer had a servant, much like an apprentice …

Discovering Molineux. A lot of tightening still to be done to make room for the illustrations I wanted in the available space. And the business of revision went on to the end. The first set of page proofs had arrived when I discovered by chance a portrait of Isaac’s master, Robert Molineux, at Otago University in New Zealand. I’d imagined Molineux as a slightly rough ‘tarpaulin’, with a Lancashire accent. He came from Liverpool. His executors were a shipwright and a carpenter, and his Will was witnessed at ‘The Folly’ tavern in Rotherhithe. Yet the portrait showed him to be a sharp, intelligent young gentleman; and thus I had to somewhat reinvent his character between the first and second proofs. ‘Thee’ and ‘Tha’, for example, became ‘You’ and ‘Your.’

'Jewels of Authenticity.'

Still, all this was largely a question of refining my ideas for the book, not creatively having to shape them, as it were, from the ether. And as we came to the end of six months of production and Captain Cook’s Apprentice headed for the printer, there were two things I allowed myself to do. The first was to look at Jackie French’s book for younger readers The Goat Who Sailed the World, that came out just as I was completing my own research into much the same material, and which I dared not open earlier for fear of being influenced.

The second was to begin reading the Master and Commander books by Patrick O’Brian, the master novelist of the 18th century navy, which again I hadn’t dare peruse. What a consummate writer and sailor he is. What a relief to discover that most of my nautical descriptions were, if not exactly right, at least not wrong. And how my heart responded when I read his remark in the preface that ‘authenticity is a jewel.’

For I had such a gem to bedeck my own ideas for Isaac’s book. The National Library has a copy of Falconer’s Marine Dictionary from 1769, which was used during Cook’s third Pacific voyage. It has twelve engraved plates of ships and their component parts, and I was keen to use some of them. We all write the books we want to read, and I have always loved stories with pictures that take me back to another age, and the words to help guide me through.

It was a struggle to find the space. But in the end Captain Cook’s Apprentice has Falconer’s engravings to enrich the ideas it contains. And at the head of every chapter, as if showing the way, is the very compass rose from a book that the great navigator himself knew. A jewel of authenticity, indeed.

|