Anthony Hill’s Newsletter

Summer 2025

Dear friends

Welcome to my Summer 2025 Newsletter. In this edition:

• Soldier Boy The Play to be produced in June

• Official launch of Theatre Works 2025 season

• New work: Completing Young Digger play

• Author’s Note to Soldier Boy The Play

• Literary Awards

• Short Story: Dance

* Books in print

Soldier Boy The Play to be produced

Let me start by hoping everybody enjoyed a happy and fulfilling Christmas, and express the wish for a successful, peaceful and prosperous New Year. As always, it will not be without its challenges, but grant us the wisdom and courage to face and surmount them.

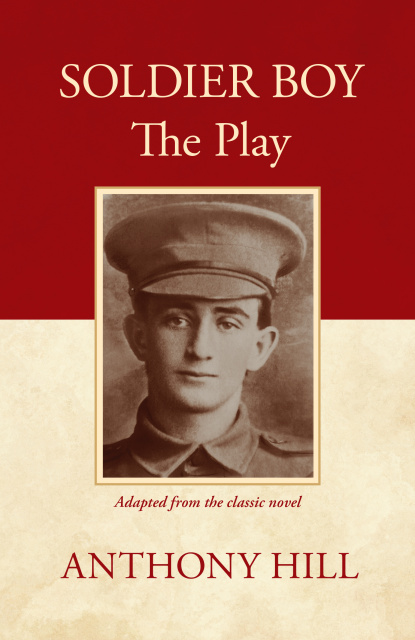

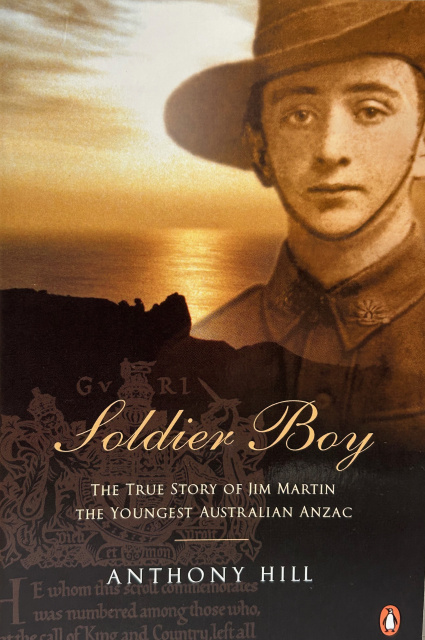

For myself, the old year finished on a tremendous high, with news that my play Soldier Boy, adapted from the successful 2001 novel of the same name, has been accepted by the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, and placed on the VCE 2025 Drama playlist.

It was followed by the equally exciting announcement that, as a result, Soldier Boy will be professionally performed in Melbourne by Theatre Works over two weeks from 20 June. The producer is Dianne Toulson, the Executive Director and Creative Producer at Theatre Works. I know we’ll be in good hands for this grand new adventure.

Theatre Works publicity shot:

Laura Iris Hill is dressed as the mother, Oliver Tapp as the son

See full Theatre Works announcement here

As you may know, the play tells the story of 14-year-old Jim Martin, the youngest known Australian Anzac soldier, from the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 to his death at Gallipoli from typhoid just over a year later.

This VCE play listing means that the work has the chance of wide exposure to senior secondary schools in Victoria, especially drama students, also interstate schools, opening a market for the published playbook which came out in September.

It also means, of course, that as the author I will necessarily by involved with the Theatre Works production team leading up to opening night on 20 June.

As one who has always loved the theatre, it will be the achievement of a life-long ambition.

I always longed to be an actor as a boy, until I realised I really wanted to write the words the actors said.

As a novelist you have the best of both worlds, for all the stories act themselves out on the stage that sits just behind everyone’s forehead.

Now I will realise it in fact, and for that I am profoundly grateful.

Acknowledgements: In saying that, I have two people in particular to thank. The first is my cousin, Laura Iris Hill, a fine classical actor, who returned after 11 years in New York just as I finished the first draft of Soldier Boy The Play. Laura helped me immeasurably to redraft the script from an actor’s and director’s point of view, improving it to the state where it now stands.

The other big acknowledgement is to Belle Hansen a producer at Theatre Works, who took the play and ushered it successfully through the curriculum process. Without her assistance, it could never have come as far as it has.

Soldier Boy is now among six works on the playlist to be performed this year, one of which must be seen and assessed by VCE (Years 11-12 ) Unit 3 Drama students.

I am conscious of the high honour for one who has not written a work for the stage these past 30 years.

I am conscious of the high honour for one who has not written a work for the stage these past 30 years.

A tribute too, to the power of the story of Jim Martin, which over the years has become an iconic Australian story of war, youth and family.

It’s also an acknowledgement to his extended family .

Through Jim’s great-nephew, John Harris of Canberra – and his late father before that – I have been supported over the years in telling the young soldier’s story to student and adult audiences around the country

The novel, first published by Penguin Random House in 2001, has already sold over 100,000 copies.

It is my hope now that the success of the play will lead to a renewal of interest in the novel.

The Announcement

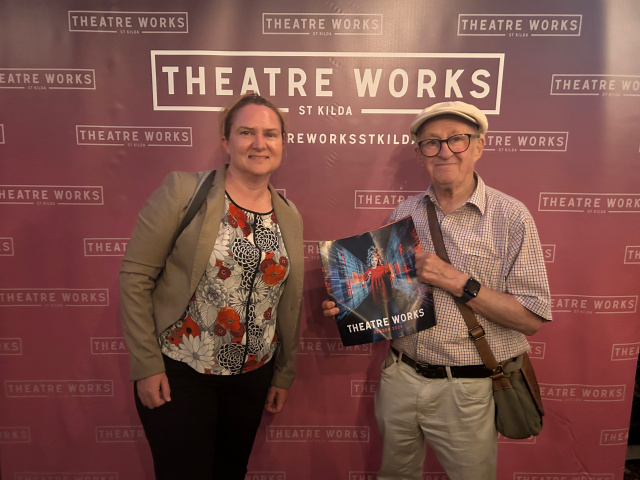

I went with Laura to the announcement at Theatre Works in mid-December of the 2025 season which includes the Soldier Boy play.

I entered the auditorium as a rather nervous old bloke, unknown to 99 percent of the audience. I came out to be congratulated by people as a playwright. I sensed during the evening that something quite unexpected was happening, but I didn’t anticipate this.

Novelist and playwright. What better Christmas gift? It will do me.

Laura Iris Hill and Anthony at the Theatre Works announcement in December

Laura and Belle’s great contribution to the play I have already acknowledged. Let me also give sincere thanks to Andy McDermott of Publicious Book Publishing, who saw me through the technical thickets of novice self-publishing, the designer Cathy Larsen, and Kristin Gill who has been helping me with the marketing.

Working with Cathy and Kristin has been quite like Penguin old home week. We three worked together during the publication of Soldier Boy the novel all those years ago. Profound thanks also to Robin Walls who edited the play script; Sarah Read and Jane Pulford who wrote the excellent Teacher’s Notes; Ali Watts and Sarah McDuling of Penguin Random House who have supported me with the project from the beginning.

New Work: Young Digger The Play

The success of Soldier Boy The Play so far has encouraged me to pull out the draft of the companion play Young Digger, determined to complete it this coming year.

The first draft has been finished, but from all that I have learned from Laura with Soldier Boy, I realise there is still much to do developing the sub-plot concerning the family at home in Queensland against the background of the returning soldiers in 1919.

This was the time when Spanish Influenza (the "plague”) came to Australia – as Covid did 100 years later – with masks, compulsory inoculations, quarantine and State border closures – and there is more to say with many contemporary resonances.

The draft has been sitting in a drawer these past two years while I’ve been completing, publishing and now getting ready for the production of Soldier Boy. It’s now very much back on the desk.

The draft has been sitting in a drawer these past two years while I’ve been completing, publishing and now getting ready for the production of Soldier Boy. It’s now very much back on the desk.

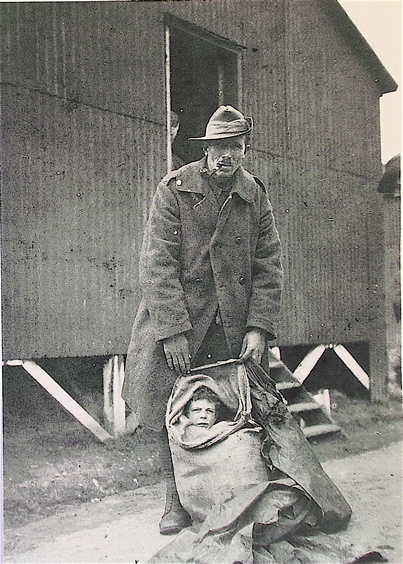

The story concerns a young French war orphan, adopted as a mascot by the 4th squadron men of The Australian Flying Corps in Germany as part of the army of occupation in 1918, and smuggled back to Australia where he was raised by Tim Tovell and his family.

Tim Tovell with Digger in the smuggling sack

The two novels were written consecutively at the turn of this century and are very much companion books. Soldier Boy concerns the outbreak of war, leaving home and finding death in the Gallipoli trenches. Young Digger is about Europe, the Armistice, coming home, and finding love and renewal from the ashes of conflict.

Likewise, the two plays were written in the white heat of inspiration: Soldier Boy between September-November 2022, and Young Digger between the end of November that year and late January 2023. For interested readers, the background follows (with apologies for the few repetitions.):

Author’s Note to Soldier Boy The Play

In September 2022, as I was helping our local theatre company paint the stage for a new production, I paused a moment, looked out at the empty auditorium and suddenly thought: “I know how I could do Soldier Boy on a stage like this.”

I’d long felt my novel about 14-year-old Jim Martin, the youngest Australian Anzac, could make a successful play or film. When it came out in 2001 with Penguin Books it was an immediate success. Even before the official publication day, it had gone through five printings, so popular was it with schools and general readership, as it still is. It won several awards, including a NSW Premier’s Award and a silver medal from the Children’s Book Council of Australia.

Hopes that it might lead to a dramatisation, however, never materialised. So that when I looked out from the Mordialloc Theatre Company stage that morning, black paintbrush in hand, the first thought was followed by a second: “I’ll write the play myself.”

Having been stage struck at the age of three (as I still am), and as an established author looking for something new to try my pen, I took up the idea immediately. Within a week I’d begun sketching scenes, and two months later I’d completed the first draft. I knew the story so well, having told it many times to schools and events around the nation, and knew which were the dramatic highlights, what worked and what information was needed to impart the essence of this tragic tale to an audience.

Not that the work was by any means finished. Writing novels is very different to writing for stage or film, and the first draft of the script needed a lot more professional input before I might consider it complete. I was extremely fortunate that my cousin, the actor Laura Iris Hill, had just returned after a decade performing in New York. Over the next year Laura worked closely with me refining and developing the script from an actor’s and director’s point of view. We went through three more drafts before a successful reading with some of Laura’s professional friends. I introduced two new characters – Jim’s friend Albert, and Rex Venables (who do not actually appear) – to give a more complete perspective on how the Great War affected many boys and their families. A second reading was held with members of the Mordialloc Theatre Company in April 2024.

Not that the work was by any means finished. Writing novels is very different to writing for stage or film, and the first draft of the script needed a lot more professional input before I might consider it complete. I was extremely fortunate that my cousin, the actor Laura Iris Hill, had just returned after a decade performing in New York. Over the next year Laura worked closely with me refining and developing the script from an actor’s and director’s point of view. We went through three more drafts before a successful reading with some of Laura’s professional friends. I introduced two new characters – Jim’s friend Albert, and Rex Venables (who do not actually appear) – to give a more complete perspective on how the Great War affected many boys and their families. A second reading was held with members of the Mordialloc Theatre Company in April 2024.

Jim, with his sister Millie on a plant stand

The current version reflects the changes and improvements made following those readings. No doubt further amendments might be made after seeing it in actual rehearsal. Even in class, teachers may find passages that could be modified, for live theatre is always a work in progress. But as it is, I hope that schools, teachers, actors and students will find Soldier Boy The Play a worthwhile dramatic text in its own right, as well as a useful adjunct to those studying Soldier Boy the novel. By investing themselves in the characters, my hope is they will have a better understanding of the people – young and old – their motivations, dilemmas and arguments both for and against the actions they took, in what has become, as Christopher Bentick notes in the Introduction, a truly iconic Australian story of family and war. The externals may have changed over the last century, but the internals of character and behaviour remain very much as they have always been.

Literary Awards

Congratulations to the winners and all shortlisted writers and illustrators in the major national literary awards announced since my last Newsletter.

Prime Ministers Literary Award

Fiction: ANAM by André Dao; Children’s: Etta and the Shadow Taboo by JM Field And Jeremy Worrall; Non-fiction: Close to the Subject: Selected Works by Daniel Browning; Young Adult: Grace Notes by Karen Comer; Australian History: Donald Horne: A Life in the Lucky Country by Ryan Cropp; Poetry: In the Photograph by Luke Beesley.

CBCA Book of the Year Awards

Older Readers: Grace Notes by Karen Comer; Younger Readers: Scar Town by Tristan Bancks; Early Childhood: Gymnastica Fantastica! by Briony Stewart; Picture Book: Timeless by Kelly Canby; Eve Pownall Award (Information books): Country Town by Isolde Martyn and Robyn Ridgeway, ill. Louise Hogan; New Illustrator: Hope is the Thing by Johanna Bell and Erica Wagner.

Miles Franklin Award:

Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright.

National Biography Award:

The Shape of Dust by Lamisse Hamouda; Michael Crouch Award: Inner Song by Jillian Graham.

Short Story:

Every literary work has something of the author in it – even sometimes a deliberately reverse image of the author’s supposed real self and opinion. This one has glimpses of the young persona reflected true enough, and how the seeds of an artist's life came to be sown.

Dance

Anthony Hill

There must have been a time before music, but Louis couldn't remember it. He knew exactly when the music came to him. It was that day the brass band played on the wireless all morning and afternoon: the same tune, over and over, so it seemed. He spent the whole day marching around the living-room, clapping his hands in delight.

He asked them about the music. They said the War was over, that was why, and don't make such a noise! Louis was only three. He didn't know about the War, except as something they talked about. Now it had meaning. It was the time he found music.

They had a gramophone in the living-room. It was in a tall cabinet, the colour of blood roses, with a handle that you turned to wind it up, and needles sharp as thorns. The records, brittle, black, were kept in their brown paper covers behind the cabinet doors. Louis could reach them easily, though he had to stretch as high as he could to put them on the turn-table.

'Be careful you don't break them,' they said. Records were expensive after the War.

There was a lot of music in the gramophone. Louis would often sit for hours, his ear pressed to the horn that was hidden behind pink silk and fretted rosewood. It was what he loved, reaching to change the records and winding the stiff handle. Sometimes people would sing in the gramophone, or play the piano. Sometimes there was a whole symphony orchestra. The music was slightly distant – slightly off-key – rising and falling with the silver needle as it ploughed the record, wavering on the scratches. Louis didn't mind. It was the essence of the sound he heard.

'Why don't you go outside and play?' they asked.

It was hard to explain why.

Of all the records in their brown paper envelopes, the one Louis loved most was the one they called Handel's Largo. He didn't understand the words the man sang in his rich, resonant voice. They said it was Italian. But the beauty of the notes, shimmering and mystical, seemed to possess him. There was, in the music, that which touched a part of Louis he didn't know was there.

Louis played Handel's Largo all the time. Until the day when, stretching on tip-toe into the gramophone cabinet, he over-balanced and the record fell, breaking on the floor in three pieces. Three black sins on the ruby carpet.

'We told you to be careful,' they said.

G F Handel

Louis wept for the discovery of grief, and loss, and guilt. The music had gone, and it was his fault.

'Don't be a baby,' they said, 'it's only a record.'

And he could not tell them otherwise.

When Louis was six, his aunt took him to the theatre. They sat with his older cousins in the front row of the dress circle upstairs. It was an exotic world of plush velvet and gold paint, with a chandelier hanging from the ceiling, that shone with crystals. Louis didn't know what to expect. Yet when the musicians in the orchestra pit began to play, and the theatre lights went down, he felt his stomach shrivel and the hairs barbed on his neck.

Throughout the play, Louis sat as one entranced. Even at interval he wouldn't join his cousins in the foyer for an ice-cream, just in case he missed something. He laughed at the clowns and the fat pantomime dame (who was really a man). He clapped the principal boy (who, so his aunt said, was really a woman), and the actor dressed up as a cat.

But it was the music he remembered, reaching up to him from the stage, and the dancing ballerina mysterious in the blue and green light. She drifted upon his vision, bathed in amber notes, at once still and fluid as lake water, or the haze in summer. It seemed to Louis, listening and watching from his balcony, that the dancer entered the very spirit of the music, and the music became one with her.

He had not imagined how such things could be.

Degas: Ballerina with Bouquet

Afterwards, when they were going home, his aunt asked if he had enjoyed the play.

'It was beautiful,' Louis said. 'I didn't want it to end.'

His cousins said they would rather go to the Saturday afternoon pictures, any time.

'I'm going to dance myself, one day,' said Louis. 'Up there on the stage in the green light.'

His cousins laughed. 'That's only for sissies,' they said.

Was it? Was the music something of which he ought to be ashamed? Couldn't his cousins sense the disturbing power of the notes, and feel the need to express it? Louis turned aside, aware that in some way he had failed a test of his sex. He may have felt the longing, but he should not have said so. Instinct told him that he had betrayed not only himself, but the music as well.

'I'm sorry,' he said. 'I didn't know.'

It was impossible for Louis to rid himself of the music. Yet it was something he knew should be kept to himself, secret and unspoken. If he couldn't have the approval of his cousins and other children, at least he wouldn't have their laughter. He didn't want to be thought different.

In his dreams, of course, Louis still saw the lady in white who danced to the music. And he still played the records on the gramophone, sometimes conducting with a stick and swaying his body, as the man in black had done in the orchestra pit.

From time to time they would watch him from the kitchen door and, smiling, say he was a real little musician. Sensitive. Though they didn't know where he got it from. Whenever that happened – whenever he felt they were looking at him – Louis would stop, embarrassed, and say it was nothing. It didn't matter. And he'd run outside to the yard.

When he was seven, Louis spent a week of the Christmas holidays with family friends and their children at a beach-house they rented. They swam and built sand-castles before knocking them down. They flicked each other painfully on the skin with the wet tips of towels.

Boys being boys; but Louis was no good when it came to playing cricket on the tidal bar. He was clumsy with the bat, and dropped easy catches.

'Stop picking on him!' the woman called from the shadow of a striped umbrella. 'He's smaller than you are.'

'Useless kid,' muttered the eldest boy, who was nearly thirteen and already with fine traces of hair on his upper lip. 'No good for nothing.'

There was no music either for the whole week, except for the hit parade on the wireless, and that wasn't the same. Not like the gramophone, or the orchestra lit with little lamps in the pit of the darkened theatre. Louis began to miss it.

On the last day of the holiday, the family went for an afternoon walk along the beach to the township. Louis had a touch of the sun, and stayed behind for a rest to get over the sick feeling.

'We don't want you getting sunstroke before you go home,' said the friend. 'They'd never forgive me.'

Louis lay on his bed, with the blinds down, trying to sleep but unable to. A melody, such as the white lady danced, kept going round and round in his head, and would not go away. At last, he got up, and wandered into the front room.

There was a radiogram, a new one, that worked by electricity and you didn't have to turn any handle. There were also some records in brown paper covers; but the eldest boy had dismissed them as 'classical stuff', and Louis dared not look. Now, alone in the house, he took them out and examined the labels. Handel's Largo was not among them. Nor did he know the other names, as best he could read them. At last he selected one by somebody Bach, and put it on.

The music, when it came, shocked him with its power. It was an organ, such as Louis had once seen and heard playing in a church. Yet nothing had prepared him for this: a scale of slow, deep, downward notes, that seemed to descend by steps through his listening mind and into the deepest recess of his body. He felt himself tremble at the harmonies, every fibre of being alive with tension. When Louis felt he could physically bear it no longer, the organ burst upon him with a cascade of sound – the notes flashing and breaking with all the brilliance of a great river spilling down a waterfall.

The music, when it came, shocked him with its power. It was an organ, such as Louis had once seen and heard playing in a church. Yet nothing had prepared him for this: a scale of slow, deep, downward notes, that seemed to descend by steps through his listening mind and into the deepest recess of his body. He felt himself tremble at the harmonies, every fibre of being alive with tension. When Louis felt he could physically bear it no longer, the organ burst upon him with a cascade of sound – the notes flashing and breaking with all the brilliance of a great river spilling down a waterfall.

J S Bach

So, too, did Louis have to release his own energies. He began to dance, not as the lady in white had done, but with his own youthful vigour. Making it up as he went. Slowly to begin with. And then, as the music flowed into him, with gathering force until he was spinning about the room – throwing out his arms and legs – imagining himself up there on the floodlit stage – expressing, he cared not how, all the joy and wonder and strength of the music that now demanded to pour out.

He couldn't help himself. For those few minutes Louis was seized by emotions he neither knew nor understood.

Until.

Until turning with the last overwhelming chords of the organ, Louis saw the faces of the other children pressed against the window, noses flattened, staring in at him and pointing. Laughing as though at a freak fit only for the loony bin. Laughing fit to burst.

He stood there for a moment gazing back at them, the dying notes falling and smashing in black fragments on the floor. Until he was alone again, unable to say anything the others could possibly understand. He didn't have the words, and they wouldn't have helped.

Louis ran to his room with the drawn blinds, and fell on the bed. His face burned with shame. He put his hands over his ears, but he couldn't shut out the taunts, 'Hey Lou-Lou, give us another poppy show!'

'I told you,' said the eldest boy, 'he was a sissy kid.'

Even the woman said he was 'a strange boy' who suffered the sun. Whether this explained, or was an excuse for his behaviour, Louis didn't know.

In any case, it was too late.

For a second time he had failed both himself and the music, and now there was no hiding it. His poppy show had seen to that. He couldn't even say any more that it didn't matter, because it did. To everybody.

The music had claimed him and, by the way he responded, it had marked him as somebody different – 'a strange boy' – a sissy kid to be mocked. And Louis knew he would have to endure the burden of that for the rest of his life.

Slightly revised from Growing Up and Other Stories (Ginninderra Press, 1999) Notable Book CBCA.

Books in print:

Personally-signed books still in print can be ordered through the website here.

• Animal Heroes ($33 plus $11.50 postage) print on demand.

• The Burnt Stick ($17.00 plus $3.60 postage).

• Captain Cook’s Apprentice ($33 plus $11.50 postage) now print on demand.

• The Investigators ($33 plus $11.50 postage).

• The Last Convict ($33 plus $14.50 postage).

• The Story of Billy Young ($23 plus $11.50 postage) print on demand.

• Soldier Boy ($20 plus postage $3.60).

• Soldier Boy The Play ($21.50 plus postage $4.50)

• Young Digger ( $30 plus postage $11.50).

I will refund any excess postage if multiple books are purchased.

Books out of print:

I have a very few copies left of some of my older titles that are now out of print. They include Antique Furniture in Australia; Growing Up & Other Stories; River Boy; and a couple of Harriet and Spindrift. If readers are interested in any of them, please contact me directly at anthony@anthonyhillbooks.com and I’ll let you know prices, postage and payment.

The next Newsletter will be the Winter 2025 edition, after Soldier Boy the play production.

With every good wish

Anthony

Photo credits:

Soldier Boy the play announcement courtesy Theatre Works; book covers courtesy Anthony Hill, Penguin Random House; Young Digger photographs courtesy the Tovell family; Soldier Boy courtesy the Martin family; Bach and Handel prints Hill collection; Degas Ballerina with Bouquet, Wikimedia Commons public domain.

www.anthonyhillbooks.com