For Love of Country

Q&A with Anthony Hill

In his brilliant new biographical novel, For Love of Country, Anthony Hill tells the story of one resilient, funny and charmingly ambitious Australian family torn apart and bound together by the two World Wars.

1. Anthony let’s start with Captain Walter Eddison; tell us a little more about his war service; he first started with the 2nd Light Horse Regiment on Gallipoli, he witnessed the slaughter of his comrades at Fromelles and was hit by a gas attack at Villers-Bretonneux, in France in 1918 while serving as part of the 56th Battalion Australian Imperial Force. He seems remarkably lucky to have survived, what were the long-term ramifications on his personal life and that of his family?

Walter Eddison was indeed fortunate that the gas he inhaled was not lethal, and that the dose seems to have been relatively small. It was enough, however, to put him in hospital for three months. He didn’t return to the front but had a desk job as quartermaster for the rest of the war.

Walter Eddison was indeed fortunate that the gas he inhaled was not lethal, and that the dose seems to have been relatively small. It was enough, however, to put him in hospital for three months. He didn’t return to the front but had a desk job as quartermaster for the rest of the war.

As his strength returned he went back to farming, migrating to Australia with his family in 1919. Even then the after-effects lasted for the rest of this life: he would become breathless and tired easily – increasingly so as he aged.

I’ve necessarily had to reimagine the exact circumstances of the gas attack, based on the battalion’s war diary which records the event. I was struck how, when the gas masks were inspected a few days later only ‘very few were found to be defective!’ Unlucky for the men wearing those few. Still, there were many points at which the masks could become frayed in the stress of active service.

I also used the gas mask as a metaphor for Walter’s internal distress as each of his sons died in the Second World War. He didn’t express his emotions in words – he usually left the room when his sons were mentioned – but his feelings ran very deep.

2. After a couple of false starts in their new country (Bobingah & Cooma) the Eddisons become one of many soldier-settlement families to make a go of farming the land in Woden Valley: can you explain what these soldier-settlement packages offered by the Government were, and their rate of success?

Soldier-settlement schemes were established towards the end of the First World War (and also the Second) to provide acreage on which returned servicemen and their families could (hopefully) establish a living for themselves. It was part of State and Commonwealth pledges to create a ‘land fit for heroes’ for those who’d sacrificed so much in the Great War.

Soldier-settlement schemes were established towards the end of the First World War (and also the Second) to provide acreage on which returned servicemen and their families could (hopefully) establish a living for themselves. It was part of State and Commonwealth pledges to create a ‘land fit for heroes’ for those who’d sacrificed so much in the Great War.

The trouble was that many of the blocks were too small or the soil too poor to sustain a proper living. Many of the settlers lacked sufficient capital or farming skills to make a go of it. Many city-dwellers were unable to adjust to rural life. The farms began to fail in increasing numbers – in many cases the settlers just walked off the land, shutting the gate behind them.

Soldier-settlers in the Capital Territory also struggled with high rents and economic recession, but they were fortunate the Territory government was sometimes able to offer more land to make the farms viable. Rent rebates and more favourable leases eventually made it easier to survive the Great Depression. Even so, people like the Eddisons struggled until the wool boom of the early 1950s.

3. While her husband Walter, and her 3 sons all fought for the British Empire, Marion made sacrifices of her own as a “bush wife” and developed a small supportive network of women. Can you tell us a bit more about these women, their contribution was to the war effort and the developing nation, and how they were perceived by the rest of the local population?

Marion Eddison was quite an anomaly as an Australian ‘bush wife’. Her neighbours’ wives almost all had either been born to the land or grew up in rural districts. Marion, however, came from Southampton in Hampshire, from a well-to-do upper middle class family.

Marion Eddison was quite an anomaly as an Australian ‘bush wife’. Her neighbours’ wives almost all had either been born to the land or grew up in rural districts. Marion, however, came from Southampton in Hampshire, from a well-to-do upper middle class family.

Through her mother she had connections with the aristocracy and even the royal family. At finishing school Marion had been taught to make dainty cakes and sandwiches for the afternoon tea table – not how to cook stews and roasts for a hungry farmer’s family. She knew how to embroider lace doilies, but not how to darn socks and sew buttonholes.

All these things had to be learned when she went onto the land, and for a long time, she wrote, she had ‘a big hate on’. Yet she eventually came to accept it and to acquire all those skills a mother needs to be the anchor of a large family.

She always retained her ladylike manners and bearing – seeming somewhat queenly to the neighbours who always called her Mrs Eddie to her face, never Marion.

4. The novel is set against the backdrop of the founding Canberra and all the pomp and excitement that came with this – some of the highlights mentioned in your new book include … but what else was going on behind the scenes politically and socially at this time?

It’s a truism that there’s an antipathy towards ‘Canberra’ as the source of Big Government and taxes among Australians, and perhaps a resistance to reading books about the place. Yet behind the bureaucratic facades it is a place where people live their lives like everywhere else. While For Love of Country is carefully not a book about Canberra, it is the setting for much of the story.

I hoped the book might interest people in some of the early and little-known history of the place … the Naming Ceremony of 1913, the opening of Parliament House in 1927 and so on. It’s quite entertaining I think. But beyond that, I wanted to show how people coped with their ordinary lives as matters of great moment unfolded around them...

I hoped the book might interest people in some of the early and little-known history of the place … the Naming Ceremony of 1913, the opening of Parliament House in 1927 and so on. It’s quite entertaining I think. But beyond that, I wanted to show how people coped with their ordinary lives as matters of great moment unfolded around them...

Walter Eddison struggling to pay his rent and facing eviction during the Depression; Mrs Eddison selling her farm cream ‘for the Minister’ in the Canberra Hotel to raise a few extra shillings; setting off in her buggy to sew buttonholes in pyjamas with her neighbours for the soldiers during the war; fearful and weeping for her sons, like mothers everywhere, when war broke out for the second time.

Canberra is home to those of us who live there – and incidentally Australia’s ‘best kept secret’. The title For Love of Country refers not just to the Eddison family story: the book is also intended to express my own love for the land where I live and the people who also dwell there.

5. The Eddisons became a very a well-known family in Canberra, where you live, and the legacy of their influence lives on in the National Equestrian Park, Eddison House (at Canberra Grammar School) and Web Gilbert’s statue to the Desert Mounted Corps in ANZAC parade…. But when did you first learn the full extent of their story?

I first heard of the Eddison family and the sacrifice of their three sons in 1994-5, when I was writing the libretto for a choral work Spirit of Place to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the pioneer church of St John in Canberra. The Eddisons worshipped there and a memorial plaque to Tom, Keith and Jack is on the wall of the church.

I first heard of the Eddison family and the sacrifice of their three sons in 1994-5, when I was writing the libretto for a choral work Spirit of Place to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the pioneer church of St John in Canberra. The Eddisons worshipped there and a memorial plaque to Tom, Keith and Jack is on the wall of the church.

When I was casting around for a story that might encapsulate the experience of the returned soldiers after the First World War, my cousins John and Esther Davies suggested the Eddison family. I immediately took it up: their story of the Great War, the soldier-settlement schemes, the Depression of the 1930s and the outbreak of the Second World War – with all the tragedy that meant for the individual and the country – says much about the experience of the generations in Australia in the years before and after the two World Wars of the twentieth century.

6. Tell us more about your research for this book; especially the primary source material (such as letters, postcards, telegrams, photos which you quote from in the book) – as well as your conversations with Pamela Yonge, the last surviving of the six Eddison siblings; what memories did she share with you?

I was incredibly fortunate with For Love of Country to find such a rich vein of primary source material – much of it previously unknown publicly – in the Eddison family archives, and the great willingness of Pam Yonge and her family to share it with me for the book.

I was incredibly fortunate with For Love of Country to find such a rich vein of primary source material – much of it previously unknown publicly – in the Eddison family archives, and the great willingness of Pam Yonge and her family to share it with me for the book.

I’ve never worked on a book with such an amount of original archival resources, and it was a particular challenge to me as a writer to absorb it properly and do justice to story – linking the family narrative to the broader history of Australia and the two generations that lived through it.

I’m immensely grateful to Pam Yonge, her daughter Sue Sarantos, nieces Wendy Townley, and Penny and Fionna Douglas who made available their own family material, including memories and interviews with neighbours of the Eddisons from the 1920s through to the 1970s, and sharing their memories. Much of it might have been lost, and I acknowledge their generosity in allowing me to make copies available to the ACT Heritage Library where it will be preserved for future researchers and historians.

7. One of the many skills you have as a writer is being able to cut through the historical facts and dates to bring major historical events to vivid life. In For Love of Country the whole narrative is rich with the sights and sounds – and indeed smells of the places and times you are writing about how have you managed to achieve this?

This is not a question that I can properly answer. All my life – as a child, a journalist and an author – I have been fascinated by history and also by story. In my recent books I seem to have found a way to combine the two interests.

I call them ‘biographical novels’, in which the external facts are as accurate as I can make them through detailed research, travel to locations and interviews with living witnesses. That’s the journalist at work. But the most important parts of any story are the internals of thought, speech and emotion – the inner journey which brings the characters to life on the page – and that can only come from myself and my own reimagining of the story as a novelist.

Traditional historians may be aghast; but I can only say that, when I begin to write, if Captain Cook is not talking within a paragraph or so of meeting him there is – for me and my story – something terribly wrong.

8. Anthony, you spent seven years travelling as a personal staff member for the Governor-General (first with Bill Hayden and then Sir William Deane) can you give us an insight into this part of your life; and how it gave you the kernel of an idea to start telling the stories of our fallen for a younger generation?

I first met Bill Hayden when I was working as a journalist at Parliament House in the 1970s. He asked me to become his speechwriter when he was appointed Governor-General in 1989. The job was initially for six months, but it turned into 10 years.

It’s a very privileged position on his personal staff, travelling to places in Australia you would probably never otherwise go to, and enjoying a unique perspective on pubic life. Several of my books arose from the experience. The Burnt Stick began with an anecdote I was told by an Aboriginal man at a barbeque I attended with the Governor-General in the Kimberley in 1989.

In 1995 I attended the 80th anniversary of the Anzac landings at Gallipoli with Bill Hayden. I was struck by the number of young people there: not just their presence, but also their silence. Anzac was speaking to them, too. I thought I’d like to find a story that said something to them about Anzac and about war in general. Three years later, working for Sir William Deane, I came across the story of Jim Martin, at 14 probably the youngest Anzac and almost certainly the youngest Australian soldier killed in war. That story turned into Soldier Boy, far and away the most successful of all my books, and the one from which my subsequent military books sprang.

9. You started out your career as a journalist, so a different discipline of writing to what you’re doing now; what about your own ambitions as an author; did you ever aspire to be a writer? How did you first come to be published?

I was stage struck at the age of three (I still am) and wanted to become an actor. Then I realised I wanted to write the words the actors spoke. I became a journalist as a way in to the craft of writing, and it certainly teaches a facility with words and how to tell a story.

I was stage struck at the age of three (I still am) and wanted to become an actor. Then I realised I wanted to write the words the actors spoke. I became a journalist as a way in to the craft of writing, and it certainly teaches a facility with words and how to tell a story.

What it doesn’t provide is entrée to the emotional inner life of story. It was only when I left journalism in 1977 and ran an antique shop in the country with my family, that I knew I had something to say about the world we live in.

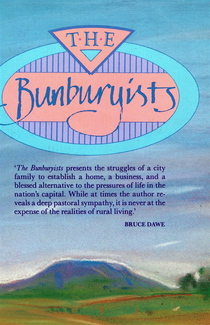

I wrote nothing of the life while we were living it: but when I returned after five years I wrote a series of articles which formed the basis of my first book The Bunburyists which Brian Johns of Penguin Books accepted. He also commissioned a non-fiction book, Antique Furniture in Australia, and that was the beginning of my long association of more than thirty years with Penguin.

10.Can you describe your daily routine as an author and researcher and what else you have to fit into your routines – apart from writing?

I’m what they call ‘a morning person’, which means that most of my creative work is done by lunchtime. Afternoons are for revision, reading-in for the next stage of the project, gardening, swimming and playing the piano.

Much of my research and note taking is done at the National Library of Australia, close to where I live in Canberra, with its unrivalled online facilities and collections of books, maps, manuscripts and photographs. Even when composing and the need is paramount to escape telephones and other interruptions, I’ll often take the iPad to a desk at the Library to complete the work started earlier that morning.

Original composition is generally done in the early hours – anytime from 5 o’clock onwards when I wake, tap away in bed on the little iPad and send the work to myself by email for later editing and revision. I don’t write for any set length of time but have a minimum target of 200 words a day: it is often more, but never less. It means each day one more page gets added to the pile.

The other part is that I always stop – always, invariably – when I know what the next sentence is to be. The rest of the day is letting it roll around in the unconscious, building on what has gone before and laying the course for what is to come next. Frequently I’ll dream it, so that when I wake the following morning the next words are usually in the mind ready to be tapped out and emailed to myself. Certainly the technique helps me to avoid the horror of the black hole of writers’ block, from which neither light nor words can escape.

11.And what’s next? Are you writing/researching anything else at the moment?

Yes, there’s a convict story I have long wanted to write. I’ve twice put it aside to work on The Story of Billy Young and For Love of Country. Now it’s the convict’s turn. He’s becoming very insistent, and after five military books I think it’s time for me to turn to another subject.

I’ve done some preliminary groundwork, but the serious research and composition will start next year, once I have For Love of Country and all the associated post-publication work out of my system. As for the title and the convict, ask me in three years’ time.