Anthony Hill’s Newsletter

Christmas 2015

Dear friends

Dear friends

Welcome to the Christmas edition of my newsletter. In addition to the Holiday Short Story, Pigs, I’ve got some great news to share with you:

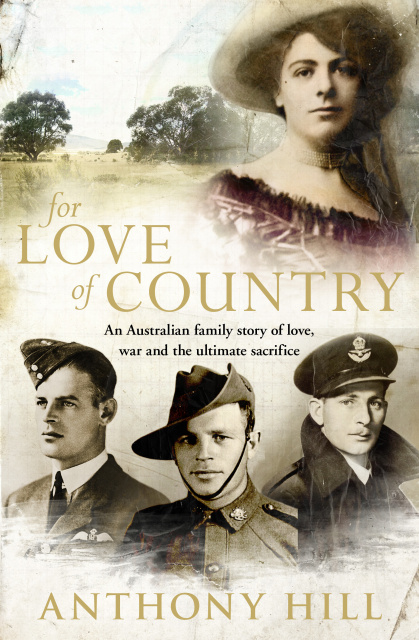

* Sneak preview of the cover of For Love of Country

* Young Digger updates

* Animal Heroes going out of print

* Literary landmark photos from England

* Prime Minister's Literary Awards

For Love of Country cover

A wonderful surprise arrived from Penguin a few weeks ago: the cover design for my new book For Love of Country, to be published in March next year.

Personally I think it’s marvellous, summarising in a single image so many elements of this family saga, spanning two generations and two world wars.

Personally I think it’s marvellous, summarising in a single image so many elements of this family saga, spanning two generations and two world wars.

Central to the story and to the cover is the photograph of Marion Mills as she was aged about 20 – the Edwardian beauty and daughter of a sea captain’s family with connections to the British aristocracy, who fell in love with a farmer’s son, Walter Eddison … and married him despite her family’s objections.

To better their prospects, Walter came to Australia looking for land just as the First World War broke out. He joined the army instead: serving at Gallipoli with the light horse, and later with the infantry in France where he was gassed. Not badly, but enough.

Returning to Australia in 1919, Walter drew a soldier-settler’s block in Canberra. And it’s the story of this family – three sons and three daughters growing up on the land in the years before the Second World War, and the terrible price that was paid in that conflict, that forms the last two parts of the book.

For Love of Countryis scheduled to be published on 23 March next year, with copies available in the shops from the beginning of April. It’s a big book, and the price will be about $35.

I’ve opened a list for readers who’d like to order an author-signed copy of the first edition once they’re available. If you’d like to add your name please send me a note to anthony@anthonyhillbooks.com. Don’t forward any money yet. I’ll send you a reminder closer to the date, together with the actual price and postage costs if you wish to go ahead.

Meanwhile, the page proofs arrived last week, and I’ve spent recent days reading closely the double pages spread on the dining table. I must say the editor and typesetter have done a great job, and there’s very little to correct. And if I might add, the story doesn’t read too badly either.

Young Digger

Not long afterwards a second book cover arrived: this one for the new edition of Young Digger, which is due for publication in June next year. I won’t reveal it yet, for I don’t want to draw attention away from For Love of Country.

But by way of a not-too-difficult clue, those of you who read the Winter newsletter last year here,will recall the fascinating photos of the little French war orphan and the airmen who brought him home in 1919, discovered by a Melbourne reader, David Daws, in his father’s album.

Well, one of them forms the basis for the new cover. I wonder if you can guess which it is?

Meantime, I’ve had a couple of very successful visits to look for material for the Introduction to the adult edition. The first was to the re-formed 4 Squadron at RAAF Base Williamtown NSW, where Wing Commander Harvey Reynolds and his staff made me most welcome. They’ve taken the mascot of the original 4th Squadron to their hearts, and indeed the gravestone from Digger’s old tomb (replaced in 2009) stands outside the squadron’s headquarters.

Meantime, I’ve had a couple of very successful visits to look for material for the Introduction to the adult edition. The first was to the re-formed 4 Squadron at RAAF Base Williamtown NSW, where Wing Commander Harvey Reynolds and his staff made me most welcome. They’ve taken the mascot of the original 4th Squadron to their hearts, and indeed the gravestone from Digger’s old tomb (replaced in 2009) stands outside the squadron’s headquarters.

In RAAF uniform, signed by Digger 1928

I also visited Sally Elliot in Brisbane, whose grandfather Tim Tovell was one of the two brothers who brought Digger home. We spent a grand day going through the memorabilia again, and I found a number of photographs of the boy and his adoptive Australian family that were new to me. We’ll be able to use some of them in the new edition.

There were also a few of the original 4th Squadron with names written on the back. I’ll send copies to Wing Commander Reynolds. They’ll be very useful for those compiling the Squadron archives, for next year marks the centenary of its formation as part of the Australian Flying Corps during the Great War.

Literary landscapes

Keats’ Walk

Just outside Winchester is one of the most celebrated – and anthologised – landscapes in English literature.

Just outside Winchester is one of the most celebrated – and anthologised – landscapes in English literature.

It’s a path the leads for a mile or so among the water meadows beside the River Itchen – one of those shallow, swift-flowing chalk streams of southern England – from the city to the medieval church and alms houses of St Cross.

Here in September 1819 the poet John Keats, living in Winchester at the time, was inspired during such a walk to write his famous ode To Autumn:

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun…

It’s since become known as Keats’ Walk, and is certainly a favourite place to visit whenever we’re visiting family in England.

The walk starts off a street near the cathedral, and leads past the handsome buildings of Winchester College on the other side of the river … past open fields and lawns…

The walk starts off a street near the cathedral, and leads past the handsome buildings of Winchester College on the other side of the river … past open fields and lawns…

… Beyond a bridge and an old stone mill house … through thickets of trees reflected in the water where tiddlers dart among the green waterweed tresses.

It really is as lovely as Keats rhapsodised; and we were accompanied on part of the way by a pair of white swans who met us near the path that leads across the field to St Cross – which is another splendid literary landscape in itself.

I’ll tell you next time.

Holiday story

Here’s a short story from my 1999 collection Growing Up and Other Stories. It doesn’t say much about Christmas I’m afraid – but it does tell us something about the business of learning to become a writer in the 1950s, and is certainly written from painful experience. I hope you enjoy it.

Pigs

Anthony Hill

Eric liked pigs.

He always thought that, when he was old enough to do what he wanted, he would buy a farm and keep pigs. Not chooks or sheep or anything like that. He wasn't interested. Just pigs.

He always thought that, when he was old enough to do what he wanted, he would buy a farm and keep pigs. Not chooks or sheep or anything like that. He wasn't interested. Just pigs.

If Eric had his way, he would have kept a pet pig in the backyard. But his parents said it was against Council regulations to keep pigs in the suburbs. They were supposed to be dirty, and the neighbours would complain. Which Eric thought unfair. It was all right by the Council to keep chooks, and sometimes even a goat, in the backyard - and they stank, didn't they? Besides, pigs were not naturally unclean. Left to themselves, they were as hygienic as any animal. Only uncaring people allowed them to become smelly and revolting.

Whatever others might say, Eric thought pigs were attractive and amusing and very good company. Every year, when they went to the Royal Show, he would go straight to the pig pens and spend a lot of time admiring the Berkshires, the Wessex Saddlebacks and the Large Whites. Until his parents threatened to get physical if he didn't hurry along. Eric didn't think that was very fair, either.

There was another reason why Eric liked pigs. His teacher, Miss Genevieve Monk, had a rubber pig stamp that he greatly envied. Actually, Miss Monk had a whole set of animal stamps in her desk drawer. There was a chicken stamp, a sheep stamp, a dog, cow and horse stamp, like a farmyard. Miss Monk stamped them on your exercise book, from the ink pad, to show approval for your work. Some teachers have gold and silver stars. Miss Monk had livestock.

The pig stamp was the best, and so was not given very often. When it was, Miss Monk generally wrote the word Excellent next to it in red ink, with her neatest copperplate hand-writing. The chicken stamp was the worst. Well, it wasn't as bad as not getting any stamp at all, or even having to put out your hand for the strap if you really made a mess, like the boy who sat next to Eric. Miss Monk was strict with her class. The strap usually came out of its drawer at least once a week.

Eric had never had the strap. But then he had never had a pig stamp, though it was his dearest wish. He tried to behave and to do his best copperplate writing in the exercise book, but it was never quite good enough. He had a lot of chickens and sheep with the words, You Must Try Harder. Once, he even got a horse with the remark, Improving! Yet the next week it was back to the chooks and the sheep. No wonder he wasn't interested in them.

The trouble was the pens: the writing pens, not the pig pens.

In those days, you sat in school at a desk with a sloping front and a lift-up lid. Sunk into the top of each desk was a white china ink-well. It was filled every morning by the ink-monitor, from a bottle of blue-black ink with a tube and a rubber stopper. The pens had wooden handles and a steel nib that spread apart like legs when you pressed down too hard, leaving blobs and blotches on the paper. Blobs and blotches displeased Miss Monk, to say nothing of inky finger-marks over everything.

At most schools you didn't start using pen and ink until third grade. Before that it was pencils, or slates that squeaked when you wrote on them. But Miss Monk believed in starting children early. Pencils, she felt, were for babies, and the scratching slates set her teeth on edge. Besides, they were no good for learning copperplate writing, her real gift to education. With Miss Monk, you began using pen and ink in grade two.

Over and over again her pupils would practice the difficult strokes.

'Keep your hand nice and round,' she would say, showing them what she meant on the blackboard. Nice round shapes, written lightly on the up-stroke, heavily on the down-stroke, with a neat curly tail at the end of each letter. Like a pig.

wwwwww

The class would copy them into their exercise books ruled with three lines (two green ones, and a red line in the middle as a guide to placing the loops in hard letters like b and d). Perhaps you still have such books, and you have to fill whole pages with

wwwwww

But not in copperplate (light on the up-stroke, heavy on the down-stroke), and not with steel-nibbed pens that drip and cause splotches on the paper.

Half-way through grade two, Miss Monk set her class to copy out a page from a book. It was a writing test, and she told everybody to do their neatest work. The child with the best exercise, she promised, would be given a pig stamp.

Sitting at the desk with the sloping front, Eric was determined to write out the page in his best copperplate, without an ink blob anywhere on the paper. He would be rewarded with the pig stamp, and take it home to show his parents. If they wouldn't let him keep a pet pig in the backyard, at least he would have one in his exercise book to prove that for once he had come top of the class.

Very carefully he dipped his pen in the china ink-well and wiped the nib. He stuck his tongue between his teeth to help concentration, and held the page steady with his free hand. Slowly he began to copy out the words about Betty and Bob At The Circus:

Betty and Bob sit in the Big Top. They are by the circus ring. Betty and Bob see dogs jump through hoops.

(Eric wondered if pigs could be trained to jump through hoops. He supposed not; but thought it better not to ask, in case he lost his place and spoiled the exercise).

He wrote to the end of the short paragraph. It was the nicest, roundest copperplate he had ever done, with not one mis-spelled word or an ink smudge anywhere. Eric was certain he would get the pig stamp for it and earn Miss Monk's praise Excellent!

He finished the last letter and put a full stop. As he did so, a tiny blob of black ink dropped off the end of the nib. It stared up at him, like a criticism, where the full stop should have been. After he had been so careful! Eric couldn't believe it!

'Pigs,' he said to himself.

Eric looked at the drop of wet, shining ink. He was afraid to dry it with his square of blotting-paper in case it made the blotch even worse. If only it could be made to look like a neat full stop, and not like an ugly mistake, perhaps Miss Monk wouldn't notice it.

He picked up his pen and began to shape the ink blot into a little blue-black circle. He should have left it alone. For as he fiddled with the damp ink, the splotch grew bigger and bigger, until it was the size of his fingernail. It had begun as a small, glistening point. Now it almost covered the last letter of the exercise. Worse, by scratching at it with his pen, the ink had soaked through the paper to the other side, and the steel nib had gouged a hole big enough to see through.

Eric had been so busy neatening up his full stop, that he hadn't realised the full extent of the disaster. Nor had he noticed Miss Monk glide up the aisle between the desks and stand, watching over his shoulder, as he ruined his work. It was only when she coughed that he looked up and saw her - and saw what he had done. He wouldn't get a pig stamp now! He'd be lucky to get a chicken.

The rest of the class was silent as Miss Monk held up the page for inspection, and questioned Eric like God as to what exactly he thought he was doing? Eric didn't know what to say. He had made a mistake, and by trying to fix things up he'd only made them worse. He hadn't meant it. But the words wouldn't come.

'We are WAITING,' said the voice of doom, 'for an EXPLANATION.'

'No miss ... sorry miss.'

Alone in the whole world, Eric got up from his place and walked to the front of the room. It took for ever to get there. The strap came out of its drawer. He held out his hands and, trying as hard as he could not to flinch, Eric got three cuts across each palm. It was the punishment for trying to make things better, and let that be a lesson to you!

Eric went back to his desk. The tears flooded into his eyes. But he wouldn't let them fall, not for anything. His hands were so painful, he felt he would never be able to pick up a pen and practice copperplate writing again.

'Rub them together,' whispered his neighbour, the boy who had some experience with the strap. 'It will take the stinging away. Old cow!'

The boy winked at Eric. The two had never got on much together, but at least they now had this in common. However terrible he felt, however disappointed, Eric would be the centre of attention at playtime.

For the year he was in Miss Monk's class, Eric never got a pig stamp. Nor did he buy a farm and keep pigs when he was old enough to do what he wanted. It wasn't possible. Adults don't have many more choices over their lives than children do.

But he continued to visit the pigs every year at the Royal Show. They were engaging creatures. Eric liked them.

Photo: US Dept. of Agriculture, Wikipedia

Prime Minister’s Literary Awards

Warm congratulations to the winners and shortlisted books in the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards announced on 14 December. The winners were:

· Fiction: The Golden Age by Joan London (Penguin Books)

· Poetry: Poems 1957-2013, Geoffrey Lehmann (UWA Publishing)

· Australian History (joint): Charles Bean, Ross Coulthart (HarperCollins); The Spy Catchers – The Official History of ASIO Vol 1, David Horner (Allen & Unwin)

· Non-Fiction (joint): John Olsen: An Artist’s Life, Darleen Bungey (ABC Books, HarperCollins); Wild Bleak Bohemia: Marcus Clarke, Adam Lindsay Gordon and Henry Kendall, Michael Wilding (Aust. Scholarly Publishing)

· Young Adult: The Protected, Claire Zorn (UQP)

· Children’s: One Minute Silence, David Metzenthen & Michael Camilleri (ill.) (Allen & Unwin.

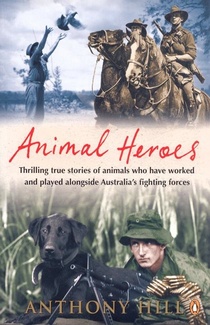

Animal Heroes out of print

One new book is spread out in proof sheets on the dining table … and another disappears.

I’ve just heard from Penguin that my 2005 book of short stories Animal Heroes is going out of print. It wasn’t altogether surprising. Sales to the schools have slowed, although I still find it very popular at my market stall. Perhaps one day we may revisit it, as with Young Digger.

Meantime I’ve just ordered in the last remaining copies. I’ll have them available to sell after mid-January until stock runs out. The price is $20 plus $7.50 postage (for which I apologise, but the thicker paper has turned it – just – into parcel size.)

Animal Heroes of course is still available as an eBook.

Please contact me direct at anthony@anthonyhillbooks.com. The book comes with a complimentary bookmark, and I will sign it as you wish. Excess postage for multiple books will be refunded.

The Autumn newsletter will come out in early March with full details of For Love of Country. Until then, with every good wish

Anthony

http://www.anthonyhillbooks.com