Anthony Hill’s Newsletter

Summer 2018

Dear friends

Welcome to my Summer newsletter. In this edition:

* Soldier Boy sells 100,000 copies

* Convict Story: rounding the turn

* Horrie the Wog Dog: Moody’s Tale

* Cook commemorations * Young Digger centenary

* Literary Awards * Books in print

* Christmas story: Limelight

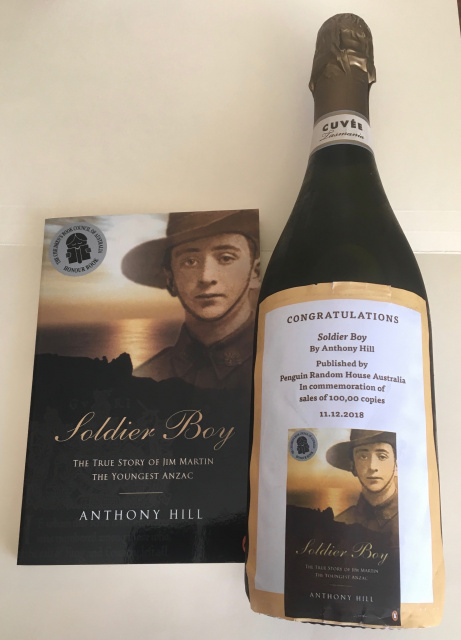

Soldier Boy tops 100K

We had an early and very happy Christmas feast last week, when Penguin Random House Books took Jill and I to lunch in Melbourne to celebrate the fact that Soldier Boy has sold over 100,000 copies. It was a great day, and we were honoured by the invitation. They told us over the table that not many Australian books reach such figures, these days.

Soldier Boy is the story of James Martin who, at 14, is believed to have been the youngest of the Anzacs and is certainly one of the youngest Australian soldiers to die in war. The book was first published in April 2001.

Soldier Boy is the story of James Martin who, at 14, is believed to have been the youngest of the Anzacs and is certainly one of the youngest Australian soldiers to die in war. The book was first published in April 2001.

It has since gone on to be by far my most commercially successful book, and continues to be widely read in schools and by the general public. For the past few years Australia Post has been ordering special printings – together with Young Digger and The Story of Billy Young – as part of its Anzac Day publications list. And these, of course, have added to the overall numbers.

The celebration lunch was attended by Penguin Young Readers publisher, Lisa Riley; Penguin Young Readers publishing manager, Kristin Gill; Author Liaison, the indispensable Deb Van-Tol. Also present was Julie Watts, my first Penguin editor, and who was the firm’s first children’s book publisher when I approached her with the notion of Soldier Boy in 1998.

Julie quickly took up the project and, with editor Suzanne Wilson, helped to turn an idea into the book that was to become a forerunner of the current wave of publications for young readers dealing with the First and Second World Wars. It was the first of the five books that I was to write on military subjects – Animal Heroes and For Love of Country in addition to the others mentioned above.

At lunch last week, they gave us a bottle of bubbly on which had been pasted a Soldier Boy label. Very appropriate. We’re saving it for Christmas Day.

It seems to me very fitting that we should toast its success in the first month following the centenary of the Armistice. After all, it brought the Great War to an end: and with it, I suspect, will come an end to the flood of centenary war books, as public interest turns to other subjects.

Convict Story: rounding the turn

My own writing has certainly turned to other matters, and for the whole of this year I’ve been fully engaged with the convict story as mentioned in previous newsletters. You may recall that in the Winter edition I wrote about the splendid research trip we made to Western Australia in June.

The amount of material I brought back has been immensely rewarding ... from the Fremantle Prison, the former Sunset Home for old men by the Swan River, Busselton, Bunbury and the remains of the timber township of Quindalup on the shores of Geographe Bay, all of which were familiar sights to the convict.

The amount of material I brought back has been immensely rewarding ... from the Fremantle Prison, the former Sunset Home for old men by the Swan River, Busselton, Bunbury and the remains of the timber township of Quindalup on the shores of Geographe Bay, all of which were familiar sights to the convict.

(You’ll forgive me if I’m not yet ready to talk about him specifically in public: the writing is not yet finished, and I need to keep the secret for a bit longer.)

Anyway, when we returned from the West I realised there was quite a significant hole in the chapters I had written already.

I’d reached the point where he landed in Perth from the convict ship, and I knew from material on the public record that he became a reader. But I had not yet properly shown how it was that this semi-literate labourer turned into someone who was able to read Mark Twain and Charles Dickens etc.

It was a problem, because this aspect of his life is very important to the novel. It meant unpicking much of what I had already done, rethinking it, and rewriting to demonstrate that, for all its horrors, the 19th Century English prison system did at least teach its inmates basic reading and writing.

It’s always a dreary business having to go over old ground. But it was worth it; and when I was able to resume from where I left off, the story had become much richer and the character altogether more interesting and robust, in my opinion.

Since then, the tale has just been flooding out – with the generous assistance, may I say, of the Curators of the Fremantle Prison who have answered a multitude of questions – and I’ve got to the Christmas break with the major part of it done. There are three, perhaps four, fairly short chapters to go. I’m not yet in the home straight, but certainly rounding the turn.

With some luck I’ll have it completed before Easter. Good going for me, as I didn’t start the book until the beginning of February this year, and I’m generally a rather slow writer. And then will come the rewrite and submission to the publisher. Always a worry – but that can wait until next year…

Moody’s Tale

Public interest in the Second World War story of Horrie the Wog Dog seems insatiable.

The original story of the little Egyptian terrier, smuggled home by Jim Moody and his signaller mates from the 2/1 Machine Gun Battalion, was written by Ion Idriess. It was first published by Angus and Robertson in late 1945 and ran through several editions. It ended with an Epitaph for the dog who was apparently seized and destroyed by the quarantine authorities.

I wrote a short version in my book Animal Heroes after I was told that the dog had instead been saved by Jim Moody, who smuggled it to a mate in the Corryong district of northern Victoria, and handed over a substitute dog to the authorities. I’ve expanded on it in the latest edition. A longer book Horrie the War Dog, containing this ending, was published by Roland Perry in 2013.

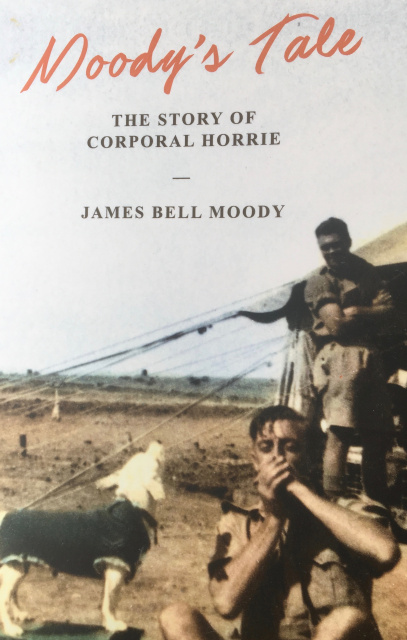

Now a new book has come out, Moody’s Tale, which is essentially the original story as written by Jim Moody in 1943-4, and from which Ion Idriess drew the material for his book.

I read Moody’s version when I was researching my story in 2005 and thought it was very well written – indeed hoped it would one day itself be published.

It appears that Moody sold his right and interest in Horrie to Angus and Robertson in 1949, and the new book has been published by Tom Thompson who acquired much of the A & R backlist including the Idriess titles.

Moody’s Tale is very well worth the read to complete the tale from the original source. Tom has also included some nice words about Animal Heroes, for which I thank him.

Copies may be obtained from ETT Imprint, PO Box R1906, Royal Exchange NSW 1225 Australia, or Australia Post bag 60038379631091. You can also use this link www.woodslane.com.au and type Moody’s Tale in the ‘Product search’ box.

Captain Cook Commemoration

The new edition of Captain Cook’s Apprentice seems to have got off to a good start following its publication in July. There has already been one small reprint on top of the initial print run; and although we have yet to see the dreaded ‘returns’, the word I have from various booksellers is that it has been selling steadily.

August marked 250 years since Cook left Plymouth in HMB Endeavour on his first great voyage of Pacific exploration. The publication was given added impetus at just that time, when it was revealed that scientists think they may have identified the specific remains of Endeavour, scuttled with 13 other ships off Newport, Rhode Island in 1778 during the American War of Independence.

The Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project (RIMAP) to examine the wreck site has been underway for a number of years now, with assistance from the Australian National Maritime Museum among others.

It will be some time before it’s confirmed if the find is Endeavour or otherwise from measurements of what’s left of the Whitby-built bark on the seabed, associated artefacts and so on; and of course, a decision has to be taken whether to raise her or not.

This work will begin next year. But the fact the archaeologists think they may have located the ship gives an extra special meaning to Cook admirers in this commemorative year.

Incidentally, the excellent exhibition Cook and the Pacific will continue at the National Library of Australia until 10 February 2019. Highlights from the Library’s own collection are supplemented by loans of paintings, maps, journals, scientific instruments, cultural, political and artistic responses to the three voyages. If you are in Canberra during the holiday season, I can recommend a visit.

Young Digger: Christmas also marks the centenary of that memorable occasion at Bickendorf airfield, outside Cologne in occupied Germany after the First World War, when the little French war orphan known as Young Digger wandered into the Christmas Dinner being held by airmen of No. 4 Squadron of the Australian Flying Corps.

‘What do you want?’ the captain asked the ragged waif. ‘I want some of your dinner, monsieur.’ And the lad they called Henri so charmed them he was allowed to stay – to become their mascot – and to be smuggled back to Australia with them when they returned home in May 1919.

Christmas Day 1918: Digger is in the dark coat middle second row

The story has lost nothing of its appeal. Indeed, my friend Anny de Decker, who lives at Ieper in Belgium, together with a number of her other colleagues have been making renewed efforts in recent months to publish articles and photographs in various European newspapers trying to find if anyone knows who the child really was.

Personally, I think the fact of Digger’s very anonymity – the Unknown War Orphan – is what gives the story much of its power and attraction. But I’ll keep you posted if anything new comes to light.

Literary Awards

Warm congratulations to the authors and artists who have been honoured in various literary awards announced since the Winter issue of this Newsletter.

The Man Booker Prize:

Milkman by Anna Burns, published by Faber & Faber.

Children’s Book Council of Australia (CBCA) Book of the Year:

Older Readers: Take Three Girls by Cath Crowley, Fiona Wood & Simmone Howell, (Pan Macmillan Australia); Younger Readers: How to Bee by Bren MacDibble (Allen & Unwin); Early Childhood: Rodney Loses It by Michael Gerard Bauer & Chrissie Krebs illust. (Omnibus Books); Picture Book: A Walk In The Bush by Gwyn Perkins (Affirm Press); Eve Pownall Award for Information Books: Do Not Lick This Book by Idan Ben-Barak & Julian Frost illust. (Allen & Unwin). Crichton Award for New Illustrators: Tintinnabula by Rovina Cai (Margo Lanagan, Hardie Grant Egmont).

Prime Minister’s Awards:

Fiction: Border Districts by Gerald Murnane; Australian History: John Curtin’s War: The coming of war in the Pacific and reinventing Australia Vol. 1 by John Edwards; Young Adult: This is My Song, by Richard Yaxley; Children’s: Pea Pod Lullaby by Glenda Millard and Stephen Michael King illust.; Non-fiction: Asia’s Reckoning: The struggle for global dominance, by Richard McGregor.

Christmas Story

For the Christmas story this year, I’ve taken a passage from the short story Limelight published by Penguin in my first book The Bunburyists, in 1985. The editor was Julie Watts, whom I introduced in the article about Soldier Boy at the head of this newsletter. Actually, it was one of Julie’s first edited books as well: the start of a long and happy association between us.

The story concerns the pratfalls of trying to put on an end-of-year concert in a country village hall. The organiser, Mrs Jupp, is trying to lay a cultural feast before her audience; but the amateur acts are putting the audience to sleep. To liven things up they have asked Marigold Baines to do a number. A former showgirl of advancing years, now the widow of a wealthy publican, she turns up in the full theatrical sequined rig, feathers in her hair, and carrying her little ukulele. She’s there to be laughed at, but she’s not a professional for nothing…

Limelight

… ‘How do you think it is going?’ Mrs Jupp asked, when the lights were switched on at interval and the audience got up for a stretch and a drink.

‘It needs a little more oomph, dearie,’ said Marigold Baines.

‘What do you mean, oomph?’

‘A bit of get-up-and-go, dearie. It’s all very nice … but they like some fun, don’t they?’

‘You should have had the farmers’ Swan Lake ballee,’ said Mr Evans.

‘They will laugh when they see her,’ said Peter Wilkes softly.

The laughs, however, came before that when Mr Richards’ juggling turn collapsed, as he feared it would, with an attack of nerves and his little coloured balls went bouncing off the stage. There was a wild scramble from the children, among whom signs of boredom were becoming evident, to retrieve them and throw them back.

‘It wasn’t meant to be funny,’ said Mr Richards, when he retired, covered in confusion.

No indeed. Mrs Jupp was intent on a serious evening’s entertainment, and nothing could have been more serious either in appearance or manner than the male voice choir, which Mrs Jupp personally conducted. She insisted they all wear dinner suits, and so solemn did they seem standing in line, fists clenched on their thighs and staring at Mrs Jupp unblinking by the piano as though their lives depended on it, that the audience was immediately hushed into that reverential awe which should always accompany Art. So that by the time they finished Shenandoah and Swing Low Sweet Chariot and trooped off the stage, very few people remembered to clap.

‘I don’t know what’s the matter with them,’ said Mrs Jupp, dabbing herself with eau-de-Cologne. ‘They have no appreciation.’

‘Don’t you worry dearie,’ said Marigold who was waiting in the wings. ‘Don’t you worry one bit.’

Mrs Jupp was finding Marigold’s patronising manner just the smallest bit irritating. What would she, who was little better than a barmaid, know about it? Who was she to tell a woman whose whole life had been devoted to the amateur theatre? So bad that she was good, Peter Wilkes had said. Well, Louisa Jupp could believe it.

‘I would like to see you do any better,’ she said.

But Marigold was no longer with her. She took a deep breath and counted to five slowly, just as she had always been taught, and walked into the dazzling sea of light centre-stage. The audience out there in the dark tittered and giggled. Mrs Jupp thought it was all too grotesque, for the woman’s black underwear was illuminated in the spotlight, and the rhinestones shimmered and flashed shafts of light to the back of the hall.

‘She looks like a Christmas tree,’ observed Mrs Jupp.

Marigold was where she belonged. She struck a few chords on her ukulele and began to sing When The Red, Red Robin Comes Bob, Bob Bobbin’ Along in a thin, quavering voice. An old woman’s voice. And yet there was something about it, something that was at least familiar. So that when Marigold came to the second chorus and cried out, ‘Come on boys, sing along!’ they did. And when Marigold broke into a soft-shoe routine and begin to caper on her spindly legs, the whole audience broke into applause and laughter, and called for more. So she sang Swanee and How’re You Gonna Keep Them Down On The Farm and California Here I Come. And by that time the hall was singing with her, so that it didn’t matter if her voice was strained and cracked, or that streams of perspiration were eroding her face paint. What the hell? Everybody was having a good time. Just as it used to be under limelight on the stage of the Tivoli or the Empire, when the audience was having fun and the men argued about who was taking her to Romano’s…

‘It is making a mockery,’ said Mrs Jupp behind the curtain.

But Peter Wilkes just laughed. And Mr McGarvie said it reminded him.

And then at last Marigold had finished. She walked off the stage waving her ukulele, away from the ocean of light in which she had bathed for one last time, into the coolness and the dark behind the curtain.

But the audience kept calling for an encore, until even Mrs Jupp, pushing her from behind said, ‘You had better go back.’

So Marigold went back and looked at the rows of upturned faces glowing in the reflected light of the stage. When they were quiet she sang The Kerry Dance. It was not a song she usually sang. Not in public. A plaintive, wistful air:

Oh, the days of the Kerry dancing,

Oh, the ring of the piper’s tune,

Oh, for one of those hours of gladness

Gone alas, like our youth too soon.

A bit sentimental. She could feel her eyes beginning to brim. She was tired. Time, that seemed to recede during those glorious minutes on the stage, stole back, and Marigold knew she would have to be gone herself soon. Never stay there too long, the producer used to say. Always leave them wanting more. So she gave them one last chorus of Happy Days Are Here Again, and with a few turns of a one-step disappeared behind the red curtain to recover her breath and repair the ravages to her make-up.

Afterwards in the supper room, over cups of tea and sponge fingers (for it was a tradition at the village concert that the ladies always brought a plate), it was agreed that Marigold’s performance had been a triumph. Even Mrs Jupp consoled herself that it had certainly gone down very well.

Mr Richards thought that Marigold ought to produce the concert herself next year.

‘Whatever you say,’ said Marigold.

‘I would be a little worried,’ said Mrs Jupp, ‘about that.’

Marigold lit a cigarette. ‘Never you mind, dearie,’ she replied. ‘Not with an old trouper like me.’

The Village Theatre by Peggy Earl, from The Bunburyists

Books in print:

Books still in print can be ordered through the website here

• Animal Heroes ($33 plus $8.50 postage)

• The Burnt Stick ($17.00 plus $3.00 postage)

• Captain Cook’s Apprentice ($33.00 plus $8.50 postage)

• For Love of Country ($35 plus $13.50 postage)

• The Story of Billy Young ($23 plus $8.50 postage)

• Soldier Boy ($20 plus postage $3.00)

• Young Digger ($30 plus postage $8.50)

Complimentary bookmark, signature and personal inscription are included. I will refund any excess postage if multiple books are purchased. Please advise if you’d prefer just a signature or the book signed to somebody.

The next scheduled newsletter will come out for Winter 2019.

Until then, with warmest good wishes to everyone from Jill and myself for a safe, happy and peaceful Christmas and a most successful New Year

Anthony

Photos: Book covers courtesy Penguin Random House and Tom Thompson; Christmas Day at Bickendorf courtesy of the Tovell family; The Village Theatre, courtesy of Peggy Earl’s family; Fremantle Prison cell and celebratory bubbly by Anthony Hill.

http://www.anthonyhillbooks.com