|

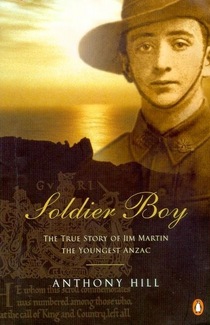

Writing Soldier Boy

Background to the book

By Anthony Hill

There were many curious symmetries involved in the composition of Soldier Boy, not the least of which were the circumstances under which it came to be written.

Gallipoli

Looking seawards from Lone Pine

For some years I had been wanting to write a book for young adults about the horrors of war. I visited Gallipoli with Governor-General Bill Hayden in April 1995, for the 80th anniversary of the Anzac Landings. Like many people, I was struck by the number of young people there, and thought I'd like to find a story that spoke not only about the Gallipoli campaign but also said something about the true nature of battle. Is it just a great adventure – or something else? For some years I had been wanting to write a book for young adults about the horrors of war. I visited Gallipoli with Governor-General Bill Hayden in April 1995, for the 80th anniversary of the Anzac Landings. Like many people, I was struck by the number of young people there, and thought I'd like to find a story that spoke not only about the Gallipoli campaign but also said something about the true nature of battle. Is it just a great adventure – or something else?

An anecdote from Vietnam was the start. I did a great deal of research. I visited several army bases and produced 20,000 words, when the whole thing collapsed under the weight of its own fiction. I was trying to write a narrative in the first person . But I've never been in the army; and while I have been to Vietnam, it was only in peace.

For three years I stared at the wreckage, hoping the idea would go away completely. But I had a wise publisher in Julie Watts, who told me not to become too dismayed. The story would come in its own time – and besides, she said, nothing in this business ever goes to waste.

There's a book in you!

So it was, in early 1999, when I was helping the new Governor-General, Sir William Deane, prepare his Anzac Day speeches for delivery at Gallipoli, that I came across the story of Jim Martin, the youngest known of the Anzacs. It was mentioned in the briefing material sent from the Australian War Memorial. Weaving Jim’s name into the speech for the Lone Pine service, I suddenly stood at my desk and said quite loudly, ‘There’s a book in you!’ So it was, in early 1999, when I was helping the new Governor-General, Sir William Deane, prepare his Anzac Day speeches for delivery at Gallipoli, that I came across the story of Jim Martin, the youngest known of the Anzacs. It was mentioned in the briefing material sent from the Australian War Memorial. Weaving Jim’s name into the speech for the Lone Pine service, I suddenly stood at my desk and said quite loudly, ‘There’s a book in you!’

Indeed there was! Enquiries to friends at the AWM showed that quite a lot was known about him. Most of his surviving letters and effects had been deposited in the collections by his family in 1985, and his story was often told to visiting school children by the education section. The wonder of it was that – apart from a photo and caption in John Robertson’s Anzac and Empire – Jim’s story had not been put into book form before.

Soldier Boy is the result: a book which, in one of those symmetries, ends where it began, with Sir William's speech at Lone Pine. I was also struck by how, so often during the research and writing, my own experience touched elements of Jim Martin’s story.

Past and present

For instance, after many enquiries I discovered that his nephew, Jack Harris, lives not far from me in Canberra. He was able to put me in touch with other family members, and bring together much new material to shed light on Jim’s family background. For instance, after many enquiries I discovered that his nephew, Jack Harris, lives not far from me in Canberra. He was able to put me in touch with other family members, and bring together much new material to shed light on Jim’s family background.

Then again, it was by pure serendipity that I found out Mr Roy Longmore – one of the last two surviving Anzacs – had also served in the 21st Battalion. Through the courtesy of his son I was able to visit him and, from the words of the living, get some glimpse into the vanished reality of the Gallipoli campaign.

Leafing through the Sands and McDougall’s Melbourne directory for 1914, I chanced upon the fact that, every day as they walked down Glenferrie Road to school, Jim and his sisters would have passed the estate agency run by my great grandfather, whose advertisement appears in the directory’s Hawthorn pages.

Howard Waring, 21st Battalion, 1915

I learned that my great uncle, Howard Waring, had served in the same Battalion and the same Company at Gallipoli as Jim Martin. They would have known each other. Howard didn’t come back from the War either, and his sister – my grandmother – carried that grief all her life.

Nothing goes to waste

Moreover, once I began writing, all the research I had undertaken (and which I still carried in my head) from the Vietnam story, began flooding back. Truly, nothing goes to waste! Images, conversations, whole slabs of sentences and paragraphs about military training dropped onto the page from the abandoned manuscript. How much easier to write of these things from the detached perspective of the third person, rather than the first!

Even more to the point, I realised from my own visits to Canungra and the Royal Military College Duntroon, that while many of the externals of military life – weaponry and transport – have changed from the First World War, the internals have not. The relationships between officers and men, and between the men themselves, are much as they ever were. And I imagine even bayonet practice and the discipline of the target range has not altered much.

In all these ways, during the composition of Soldier Boy, my own experience kept making contact with what must, at this distance, be the imagined reality of Jim Martin’s life. It underpinned much of what I was trying to do with the book: to blend the voices of the storyteller and biographer – to attempt a synthesis between the differing approaches to truth taken by writers of fiction and non-fiction, into a form sometimes known as ‘faction’ but which I prefer to call a ‘biographical novel’.

Biographical novel

Manningtree Road School

As I see it, the form requires the author, on the one hand, to remain true to the historical facts of the story so far as they can discovered – and where they can’t, to suggest some plausible explanation for what happened and why. As I see it, the form requires the author, on the one hand, to remain true to the historical facts of the story so far as they can discovered – and where they can’t, to suggest some plausible explanation for what happened and why.

External truths. In this respect, I have had to assume certain aspects of Jim Martin’s story: his visit to Aunt Mary in the country, for example, to account for why Jim described himself as a ‘farm labourer’ on his enlistment form, or, in the absence of any surviving letter, to imagine his personal experience on the Southland. I have been careful, however, not to alter any known fact; but rather to openly acknowledge these inventions and to base them on the records and eyewitness accounts of those who were there. By so doing, I hope, if new material does come to light, it will be possible to incorporate it in another edition while maintaining the intellectual integrity of the book as it appears. To this extent, Soldier Boy is grounded in external truth.

Internal truths. On the other hand, a biographical novel does permit an author to explore the inner life of the subject: to write of the myriad thoughts, feelings, emotions, doubts, confusions, contradictions and spiritual longings that are part of the reality of every human being. They are the very stock in trade of the novelist; yet they are usually denied the strict writer of non-fiction, unless they have been placed on the written or oral record (and then usually in some carefully self-edited form).

Essential truths. Thus I have felt free to imagine the thoughts, the fears, the prayers and conversations of the people in Jim Martin’s story. I based them on known statements where I could Never mind Dad, I’ll go instead! but otherwise I allowed them to flow in their own channels. And it was surprising to discover how often these fictional devices allowed me to approach what I believe to be the essential truth of a situation. Essential truths. Thus I have felt free to imagine the thoughts, the fears, the prayers and conversations of the people in Jim Martin’s story. I based them on known statements where I could Never mind Dad, I’ll go instead! but otherwise I allowed them to flow in their own channels. And it was surprising to discover how often these fictional devices allowed me to approach what I believe to be the essential truth of a situation.

By trying to re-live Amelia’s thought processes when confronted by Jim’s threat to run away, it became much easier to understand why she signed the consent form. I could see why she didn’t simply tell the authorities that her son was only fourteen. Otherwise she risked losing him for ever. Which in fact is what happened - but Amelia couldn’t know that at the time.

Amelia and Charlie Martin, 1915

By imagining Jim’s fears as he lay sick and dying in his dugout, I began to realise why he didn’t report to the medical authorities. The shame of discovery and of being stripped of everything in front of everybody, was more than the boy could bear.

The sensible thing, for both mother and son in their circumstances, would have been to do the opposite of what they actually did. But we are not always rational beings. Emotion often provides a much stronger motive for action. And the great virtue of fiction is that it helps to convince the reader of the truth of that in a way non-fiction, with its emphasis on objective ‘fact’ and external logic, rarely can.

The heart of the matter

Not many writers have attempted a biographical novel in the terms I have outlined here: even fewer in the field of literature for children and young adults. Whether or not I have wholly succeeded with Soldier Boy, I am persuaded of one thing. Given the right story, the form offers the writer a marvellous device to keep the narrative moving. It gives scope to explore an aspect of the past, to stimulate the outer action and to maintain the interest of young readers, while also allowing the freedom to explore the inner world of character, contemplation and meaning.

Such matters, I would maintain, are at the heart of all serious literature for children and adults alike. Certainly I used the same approach in another story from the First World War, Young Digger, about the Armistice and homecoming, and which I see very much as a companion piece to Soldier Boy.

Anthony Hill, February 2001

Photo Credits:

Looking down to the Aegean Sea from Lone Pine, 1995: author photo.

Soldier Boy cover: courtesy Penguin Books Australia.

Private Howard Waring, 1915, Anthony's great uncle: author photo.

Manningtree Road School, Hawthorn, 2000: author photo.

Amelia and Charlie Martin, 1915: courtesy Martin family.

|