Matthew Flinders laid to rest

I dare say many of you have caught up with the news that Matthew Flinders, the great navigator and cartographer, has finally been laid to his rest in the church at his home village of Donington in Lincolnshire.

Royal Navy seamen with Flinders’ coffin at the graveside

I spent much of Saturday night 13 July, watching the very moving and beautiful service on a live stream broadcast arranged by the local group Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home, who were strong and active supporters of the reinterment. The broadcast cut out part way through, but it was all there on Facebook next morning.

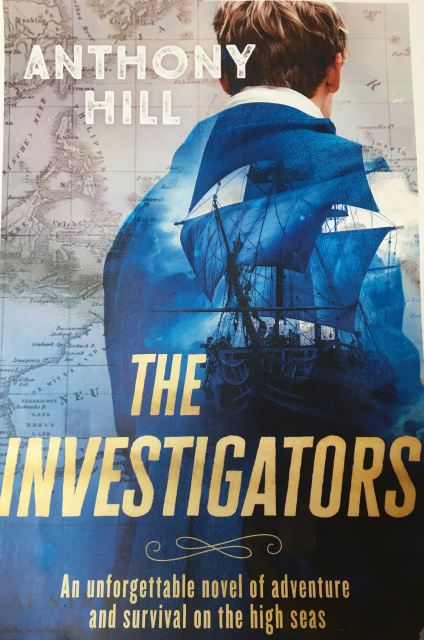

The occasion was of particular significance to me and fellow voyagers, for Flinders, his friend Dr George Bass, and patron, Sir Joseph Banks, were key figures in my last historical novel The Investigators about the first modern circumnavigation of the Australian continent (1801-03).

All three Lincolnshire men of great importance in the history of Australia’s maritime exploration, are remembered in the stained glass window at the Church of St Mary and the Holy Rood, which now also illuminates Flinders’ grave.

A fourth, Flinders’ cousin Sir John Franklin, has his own memorial at nearby Spilsby (see the Summer 2024 Newsletter).

News of the discovery of Flinders’ first grave, near Euston station in London, came during the writing of The Investigators.

I was able to incorporate it in the book, and this month’s memorable service has brought his heroic if tragic story to an honoured closure.

Conducted by the Bishop of Lincoln in the presence of the Governor of South Australia, Flinders family members and other dignitaries, the service was redolent with the Royal Navy.

Flinders was carried into the church by a party of seamen, the coffin covered with a pall incorporating both the Australian and British flags, and a wreath in the form of a white anchor with red roses.

He was lowered into his grave by sailors to the sound of bosun’s whistles, as a Captain should. And a volley of rifles was fired in salute outside.

.

Afterwards earth from his native Donington, Australia, Mauritius (where Flinders spent some seven years a POW) and London, where Matthew died in 1814 aged only 40, were sprinkled over the coffin.

Memorably, an indigenous man Laurie Bimson, a descendent of the Aboriginal leader Bungaree, who sailed with Flinders on the circumnavigation, dropped into the grave a boomerang smeared with ochre from Bungaree’s country north of Sydney and carved with his stingray totem.

Laurie is seen standing to the rear in the photo above, head bowed and wearing a hat.It was of Bungaree that Flinders spoke about his “modesty and forbearance” and wrote glowingly of his “humble friend.”

These sentiments shone brightly through the years of prejudice, and I’m glad to say I was in contact with Laurie about his ancestor during the writing of The Investigators.

It was more than fitting to see him at the service, standing with his boomerang beneath a bronze bust of Flinders the navigator.

Interestingly, the lead plaque on Matthew’s original coffin that identified his human remains, will be exhibited on loan at the South Australian Museum.

I express sincere appreciation to the Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home team for their dedication to the project. They were very helpful to me and gave permission to use some screenshots from the service.

Also to Rev. Mark John Williams, vicar of St Mary’s, for his kind advice and for sending me a copy of the Order of Service. I will keep it as a treasured memento.

Comment:

Iconoclasts

I must say that, watching the great honour being paid to their native son by the people of Donington and the wider Commonwealth, I couldn’t help but reflect on the dishonour sometimes heaped these days on the early British navigators and founders in this and other former colonial countries.

In recent years we’ve seen statues of Captain Cook defaced, cut off at the knees and scrawled with slogans such as “The colony will fail.” Flinders’ statues have not escaped the vandals, and even that of Sir John Franklin in Hobart is said to be under some question.

It’s a crude, iconoclastic age, where the colonial legacy is being discredited by some academics and activists in what seems an attempt to delegitimise the modern nation state in favour of some mythic native idyll. A time when historical novelists like myself can feel a somewhat threatened species.

It’s a crude, iconoclastic age, where the colonial legacy is being discredited by some academics and activists in what seems an attempt to delegitimise the modern nation state in favour of some mythic native idyll. A time when historical novelists like myself can feel a somewhat threatened species.

It is, I believe, a passing phase – one that is rejected by the great majority of citizens – and is in any case a hopeless cause.

To be sure, it’s one thing to re-evaluate and reinterpret the past – to acknowledge the sometimes violent displacement of indigenous people by colonial settlers. Invaders if you must.

But to try to erase history by destroying monuments, or blaming people like Cook for the faults of those who came after them, or indeed for having been men of their time, is an exercise in futility and evasion.

It was Flinders who did so much to popularise the very name of the continent Australia, and who first called the indigenous inhabitants “Australians”.

The past cannot be undone. The colony did not fail. We in the present are certainly responsible for healing as best we can the wounds we’ve inherited, and together for making a better future as one prospering nation and one self-governing people. Responsible for ourselves and our actions alone.

The past cannot be undone. The colony did not fail. We in the present are certainly responsible for healing as best we can the wounds we’ve inherited, and together for making a better future as one prospering nation and one self-governing people. Responsible for ourselves and our actions alone.

The 17th, 18th and 19th centuries were a time of European expansion, and the colonisation of Australia and the Pacific was inevitable. In my view better the British, with their ideas of political liberty and the rule of law, than some other Powers one could name.

And for that it is the great British navigators such as Cook and Flinders, with their vision and scientific skill adding to the sum of human knowledge about the world as it really is, that we have to thank.

As they did with much reverence and ceremony for Matthew at Donington on 13 July 2024.

Matthew Flinders, Mauritius 1807

Here he lies where he longed to be:

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

Robert Louis Stevenson