Following my recent Sound Tracks posts, the noted Australian journalist, author and broadcaster, Tim Bowden, has done me the signal favour of writing a series of articles on his own experience of interviewing people over more than half a century of public life in radio and television.

There’s a particular emphasis on the techniques of recording for oral history … not surprising in a man who has been behind a major series of ABC broadcasts on Australians in Antarctica, Papua New Guinea, Australian prisoners of war in Asia and – memorably – his own father. These articles will continue over the next five weeks.

I recommend them to everyone with an interest in broadcasting, interviewing and the whole sweep of oral history.

Anthony

The Question I Dread…

By Tim Bowden

Occasionally, after a long career in broadcasting and television, I am interviewed by a young reporter, who invariably asks the question I dread. ‘Who was the most interesting/famous/unforgettable character that you have ever interviewed?’

Chris Neilson in later life, with Tim Bowden

My reply is invariably, ‘It is someone you would never have heard of. A man named Chris Neilson who was a prisoner of war of the Japanese in Singapore, and who survived not only the Malayan Campaign, but a period of bestial imprisonment in a military prison, Outram Road Gaol, after three years of solitary confinement on starvation rations and daily beatings by sadistic prison guards, and who survived to tell the tale and lived into his 90s.'

The truth of the matter is that Chris Neilson is only one of many interviewees over the years I could have nominated. For one of the great joys of oral history is uncovering the stories of so called ‘ordinary’ people, whose ‘extra’-ordinary experiences would otherwise go unnoticed and unheralded. Chris’s story is a triumph of courage and a celebration of the survival of the human spirit despite seemingly insuperable odds.

Tricks of the trade...

It never ceases to amaze me how people with remarkable stories to tell, are willing to share their experiences with someone like me – often during one meeting, that may last for two or three hours. There are a few tricks of the trade of course, which are perhaps basic, but essential.

The first can be summed up in the old military adage, ‘Time spent in reconnaissance is never wasted’. In other words, research into the background of your interviewee, and (in the case of prisoners of war of the Japanese) the circumstances of that experience.

When my friend and colleague, historian Hank Nelson, and I began work on a major project for ABC Radio on the experiences of Australian prisoners of war in South-east Asia from 1942–45, I knew practically nothing about what they had been through.

This was partly because by 1980, when Hank and I began what would become an 18-part radio documentary series titled Prisoners of War – Australians Under Nippon, many of the survivors had never even spoken to their own families about what happened to them.

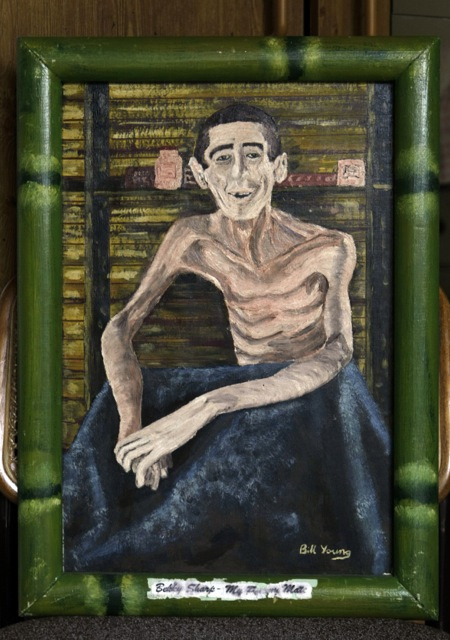

An Outram Road POW at war's end. Painting by Bill Young.

There was, unbelievably, a collective feeling of guilt that, although they had fought gallant but short actions in Malaya and other theatres, they had not been ‘proper soldiers’ as prisoners of war. This was a nonsense of course, but that is what they thought. Hank reasoned, rightly, that more than 30 years on (with most of them by then in their mid-60s) the time might have come to get them to open up. How right he was!

Reconnaissance

With Hank’s guidance, I began to read what memoirs and histories were available about the POW experience. However there was not much about. Military historians are predominately interested in campaigns and battles, not in the experiences of prisoners of war. But in the case of the Australians taken prisoner, they endured three-and-a-half years of appalling privations and slave labour that took an enormous toll.

The statistics are revealing. Of the 22 000 Australian soldiers (and nurses) who were captured, only 14 000 survived to return home. On forced-labour projects like the infamous Thai-Burma Railway, one in three Australians died in one year, 1943.

They were more at risk as POWs than on active service, and the casualties bear this out. It was high time their stories were told.

One big plus in 1982 was for Hank and I to go on a POW pilgrimage to Singapore, Malaya and Thailand with a group of survivors. Actually to stand on the abandoned track of the railway they had helped to build, and listen to them describe what had happened, was invaluable research.

Opening up

I did have a recorder with me, but did not make much use of it at that stage. Hank and I wanted to absorb as much background information as we could.

I knew from experience that you really need to sit down with one individual for several hours to get really first rate oral history testimony. Working with groups in social situations rarely produces anything of value for the oral historian.

Consequently when I did introduce myself to survivors and request an interview, people were polite but guarded. Things changed when I raised topics like the Thai-Burma Railway.

‘Were you there?’

‘Yes I was.’

‘Were you on the Thai side or the Burmese side?'

‘In Thailand actually.’

Now, I knew that the shortest straw on the Thai side of the railway was to be in either H Force, or F Force, high up in the mountains where rock cuttings had to be hewn by pick and shovel and improvised explosive charges, on the end of a torturously difficult supply line where only limited food ever arrived, and then mostly in a putrescent condition.

Now, I knew that the shortest straw on the Thai side of the railway was to be in either H Force, or F Force, high up in the mountains where rock cuttings had to be hewn by pick and shovel and improvised explosive charges, on the end of a torturously difficult supply line where only limited food ever arrived, and then mostly in a putrescent condition.

So I would ask: ‘Were you on either F or H Forces?'

My interviewee would look at me with surprise. ‘Oh you know about that do you?’

He then opened up, and began treating me as though I was a returned POW myself, and floodgates of long repressed reminiscence poured out of him. At that stage I didn’t know much else other than that these work parties had existed. But I was off and running.

* * *

In the next article Tim Bowden discusses the recording techniques that minimise the anxiety some people might have while being interviewed.

Tim Bowden’s website is www.timbowden.com.au, where copies of his available books can be ordered.

Photo Credits:

Chris Neilson and Tim Bowden, courtesy of Tim Bowden.

Billy Young's Pommy mate 'Becky' Sharpe in 1945, painting by Bill Young from a newspaper photograph. Picture by John Feder. Chris Neilson wrote out Morse code for Bill Young in Outram Road prison. See The Story of Billy Young pages 95-6.

The Changi Camera, cover courtesy Tim Bowden.