Last week’s post about Editing in Another Medium led to the further thought: what’s the method most writers prefer when setting down their original composition – writing that tantalisingly difficult first draft?

Are we still pen and paper people – Edward Gibbon’s “scribblers” – at heart? Or have we adapted completely to the electronic revolution, and happily compose as well as edit on the shining screen? Indeed, for many of us to publish, market and earn an income from our books in a strictly digital way?

Belt and braces – or, The best of both worlds…

Belt and braces – or, The best of both worlds…

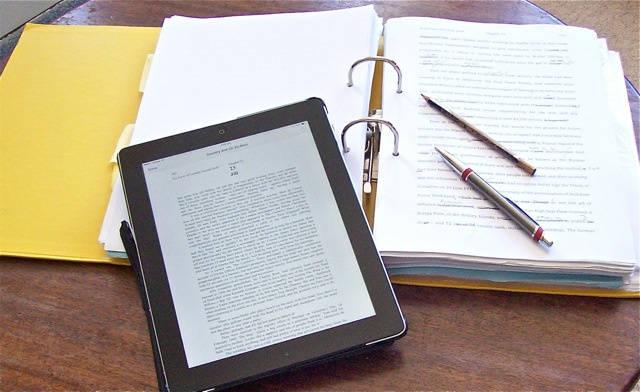

Personally, I try to straddle both worlds, though the balance of late is tipping to the new way of doing things. In fact I’ve fallen in love with the little iPad. Tapping away there in bed of an early morning and emailing the text to myself, has quite changed my way of writing books.

As a young journalist in the ’60s I had no problem writing stories for the newspaper at the typewriter … bashing them out on the keyboard, or even phoning urgent copy through to the typists directly from my shorthand notes.

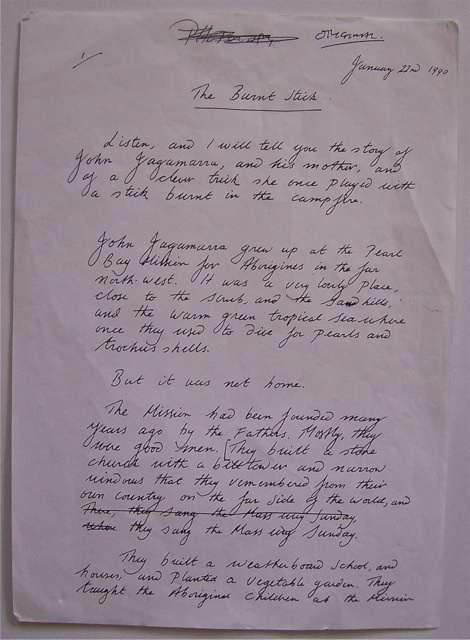

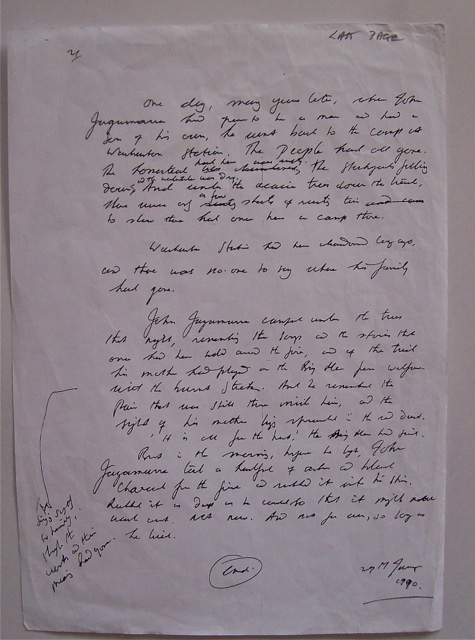

But when it came to writing my first books – “real” writing, “proper” writing, as I deemed it – they all had to be written out in ink by hand on the page before I transferred them to the typewriter and, later, to the computer. It was always black ink on plain white paper … and the first page had to be neatly written out, however much the later pages of a ms became an almost indecipherable scribble.

Scribbling: “The Burnt Stick” manuscript 1990

Other authors have their own idiosyncracies. Some prefer to write on yellow foolscap. Oscar Wilde, I read somewhere, wrote in green ink upon mauve paper! Jane Austen and her “little bit (two inches wide) of ivory”. Yet whatever the individual means, it seemed to me that something happened between the brain, the hand and the tip of the pen, that turned an idea into literature – and it was  never the same on the keyboard.

never the same on the keyboard.

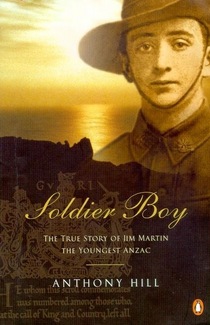

It wasn’t until my eighth book, Soldier Boy, written in 1999-2000, that I first began to compose directly onto the computer keyboard. It was strange at first, and difficult to engage the imagination.

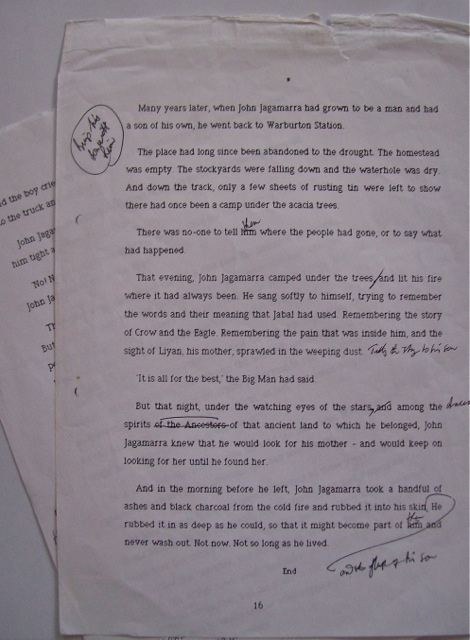

But once I began to see not only the form of the words, but the shape of the sentences and paragraphs as they’d appear on a printed page, I became much more involved. Whole sections could be moved around, and transposed from one chapter to another without the manuscript looking like a spiderweb of inky black lines.

The architecture of the book began to emerge almost from the beginning, and I found myself becoming ever more fluent at the screen. Now, all my books are composed directly on the keyboard … although I’m very careful to print out a copy of each day’s work (on the reverse side of earlier drafts, scored through with a line so as not to confuse versions), to edit the page in pencil and to keep it with the running text of each chapter.

For all the ease of manipulating electronic copy, it is often the case that, upon reflection, the first version of a passage may seem the best. Easy enough to recover in manuscript. But if it has been deleted from the screen draft without being printed, it can be difficult to remember what that best version was. So keep them all.

It’s belt and braces for me, really. All the speed and freedom of the new technology … tempered by an old-fashioned distrust of the digital siren singing its paperless song. What if the typescript were to disappear into the cloud completely?

Besides, there’s a lingering belief that the written word should be just that. Written – or at any rate printed – in black ink on a white page.